|

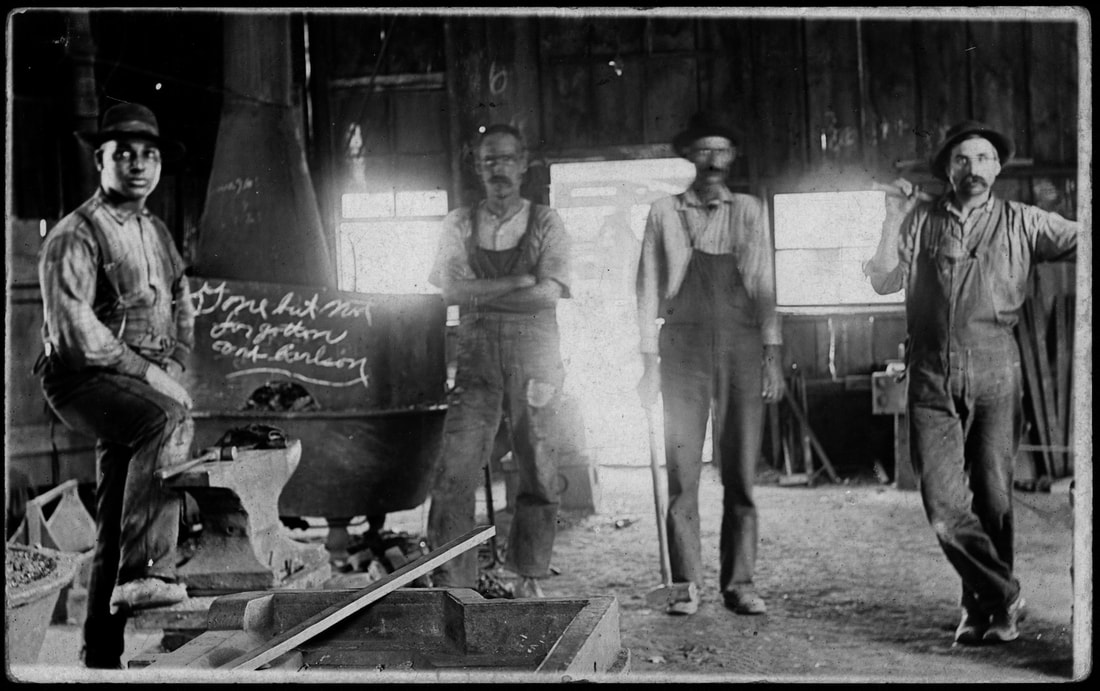

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! This week’s post marks the third and final post in our 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa (you can find the other posts here and here). This week’s post is by author Rachelle Chase. Even before moving to Iowa, the history of Buxton, Iowa, and its former residents fascinated Rachelle, and now that she has become an Iowa resident, she is determined to help share their story. Rachelle is the author of multiple fiction books and the non-fiction book, Lost Buxton. In 1900, Consolidation Coal Company established one of the most unique towns in Iowa: Buxton. Spanning 8,600 acres in Monroe County and 1,600 acres in Mahaska County, along with a population that grew to 5,000, Buxton became the largest unincorporated town in Iowa. Though the town itself was different from most other coal mining towns, Buxton is renowned for its large African American population. For the first 10 years, African Americans made up 55% of the population and remained the largest ethnic group until 1914. A Planned Town The typical mining town featured hastily constructed houses, a company store, a small school, a tavern, a union hall, and a church. Buxton was not “typical.” Buxton residents enjoyed 1-1/2 story houses which were maintained by the company, a company store that rivaled department stores, three two-story schoolhouses, a two-story high school, a three-story YMCA, and more than 10 churches. According the September 18, 1903 edition of the Iowa State Bystander, Superintendent Ben C. Buxton “designed and superintended the laying out of the town, the plans and construction of the buildings, the location and equipment of the mines, the water supply, the drainage and all the many interesting details ...” Buxton, Iowa, looking north. “Boy’s Y” (rectangular white building, left), YMCA (far left), W.H. Wells Company Store (center). The company store burned down in 1911 and was replaced with a brick building and renamed Monroe Mercantile Company Store. Courtesy: Michael W. Lemberger. A Prosperous Town As mentioned in previous posts, mining was often seasonal, which resulted in a reduced demand for coal in the warmer months. This was not the case in Buxton. Since Consolidation Coal Company was owned by the Chicago & North Western Railroad and trains required a constant supply of coal, men in Buxton worked year-round, earning $40-$100 every two weeks. “The miners received excellent pay according to the economy at that time,” said Reuben Gaines Jr., a successful African American businessman in Buxton, in an undated memoir. “In any event or manner the money flowed freely.” There was no shortage of ways residents in Buxton could spend money. They could shop at more than 40 independent businesses, plus the company store. “You could buy anything in that company store, from a diaper pin to a coffin,” said Kietzman. “The company had its own morticians and own mortuary. They had a shoe department, shoe repair department, furniture, hardware, groceries, cooking ware, clothing, and yard goods. The company store had a bank in it, the company office, a soda fountain where they served lunches.” A Racially Integrated Town Former residents—both black and white—agreed that Buxton was integrated and that any segregation that did exist, such as separate churches, was by choice. The company awarded housing on a first-come, first-served basis; 16 of the 85 company store clerks were black; black men and white men worked in the mines in neighboring “rooms”; black children and white children were taught by black and white teachers; and residents attended public events—baseball games, movies, parades, and picnics—sitting or standing wherever they desired. Believed to be blacksmith’s shop in Buxton, Iowa. Courtesy: State Historical Society of Iowa Residents also remembered interracial marriages. “There were a lot of interracial marriages down there...” said Oliver Burkett, an African American resident. “There was Charlie King, he was a black man, he married a white woman. Hobe Armstrong, he was a black man and he married a white woman. George Morrison, he was married to a white woman.” Carl Kietzman, previously quoted, was married to an African American woman. African Americans Thrived In addition to miners, there were many African American professionals and business owners in Buxton. African American professionals included doctors, lawyers, a dentist, pharmacists, constables, teachers, commercial and rental property owners, an insurance agent, company store clerks and at least one manager, a bank manager, a cigar maker, a postmaster, a mine engineer, two justices of the peace, barbers, a tailor, and many entrepreneurs. Black-owned businesses included hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, confectionaries, a bakery, drug stores, pool halls, dance halls, a music store, a photography and printing business, a meat market or two, millinery shops, and at least four newspapers. The End of Buxton By 1918, the mines near Buxton were almost completely played out and the company had moved operations to Consol, located 18 miles southwest of Buxton, and Bucknell/Haydock. By 1922, Buxton was a ghost town. Miners and their families had moved to other cities in Iowa and beyond in search of work or had moved to the company’s new towns. But by 1927, the continuing decline in coal demand and the negative perception of Iowa coal, plus labor problems, resulted in the shutdown of remaining mines. Consol and Bucknell/Haydock, like Buxton, were gone. The company store’s stone warehouse, the largest remaining structure in Buxton, Iowa in 2016. Source: Rachelle Chase For many African American residents, leaving Buxton was like stepping back in time. Jim Crow laws, segregation, extreme racism, and menial jobs awaited them, leaving many feeling like Susie Robinson. “There’s no place that’s ever going to be like Buxton,” said Robinson. “That’s the best place that I’ve ever been, Buxton.” If you would like to learn more about Buxton, Rachelle’s book, which uses rare photographs and quotes from former residents to tell its unique history, can be found on Amazon. You can also learn more about Rachelle and her books on her webpage.

I hope you’ve enjoyed our mining series as much as I have, and many thanks to our guest authors Darcy and Rachelle!

2 Comments

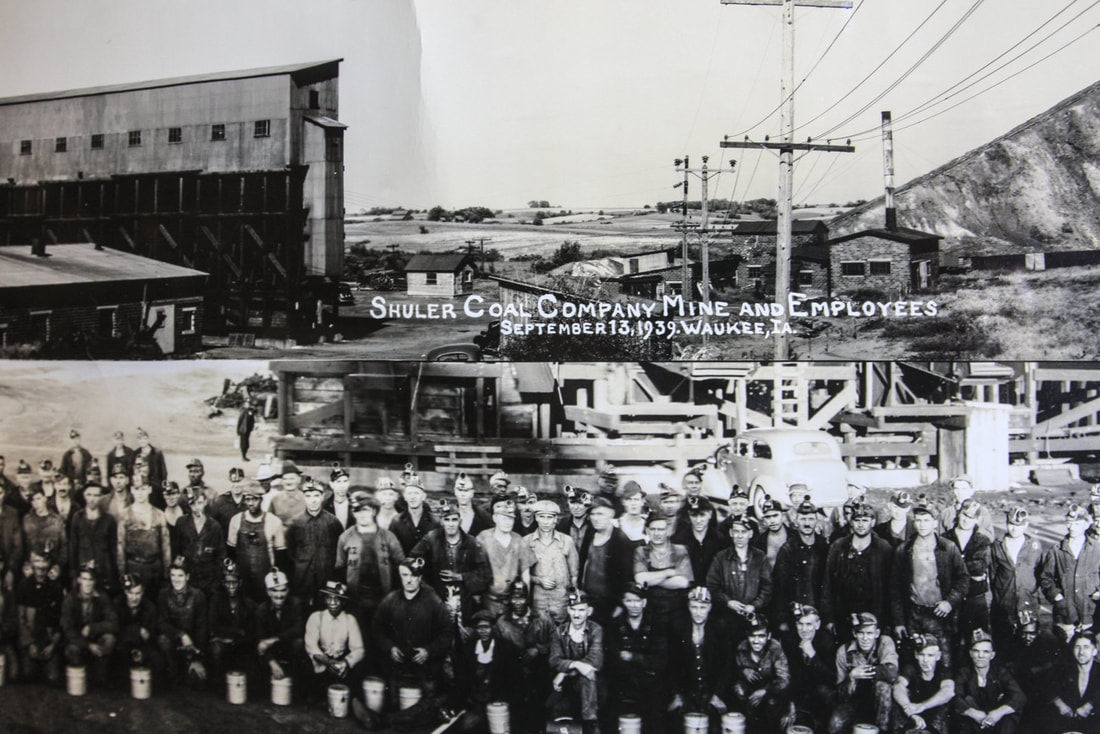

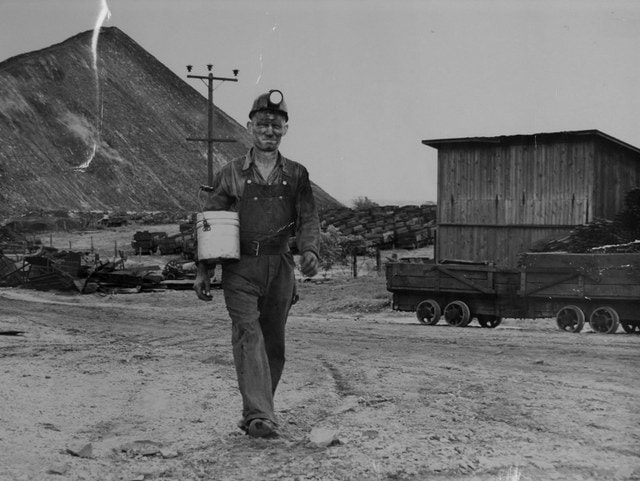

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! This week’s post marks the second in a 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa (you can find the first post here). This week’s post is by author Darcy Maulsby. Darcy is an Iowa native, former Dallas county resident, and author of three history books, including the soon-to-be-published Dallas County. Enjoy! There was a time when Dallas County was one of the most important coal-mining counties in Iowa. While this way of life vanished decades ago, the memories live on, from the Hotel Pattee in Perry to the Waukee Public Library to the many descendants of mining families who still live in the area. From Moran to Woodward to Waukee, Dallas County thrived with the increased demand a century ago for coal to power train locomotives and heat businesses and homes. Coal was a relatively cheap, plentiful energy source. With ample supplies of coal, Dallas County became a land of opportunity for immigrant miners from Europe and beyond. Coal mining started in the Van Meter area as early as the 1870s. By the early 1900s, coal was discovered in Des Moines Township east of Woodward, leading to the creation of the Scandia and Phildia mining settlements. After the Phildia mine was abandoned in 1915 and the Scandia mine closed in 1921, miners moved on to the Moran mine, which opened in 1917 west of Woodward. You might remember Moran from last week’s post. It's not on most maps today, but there was a time when Moran was a bit of a boom town. The Angus & Moran Room at the Hotel Pattee in Perry recalls the history of Moran and Angus, a once-thriving mining town east of Perry that once boasted thousands but now has only a handful of residents. Shuler Coal Mine and employees on September 13, 1939, in Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Living with danger On the opposite side of Dallas County, coal mining also transformed the Waukee area in the early twentieth century. The Harris Mine opened on September 20, 1920, just two and a half miles northeast of Hickman Road in Waukee. By 1921, the Shuler Coal Company of Davenport, Iowa opened a coal mine on Alice’s Road, one mile east of the Harris Mine. At its peak production, the mine employed more than 450 men. The Shuler Mine became one of the largest producers of coal in Iowa, and it had one of the deepest mine shafts--387 feet deep. The mine produced coal for Iowa State University, as well as for local railroads, businesses and homes. The miners worked in the Shuler mine with the help of more than 30 mules, bringing up hundreds of tons of coal per day and millions of tons of coal over the mine’s 28 years of operation. The miners’ work day often started at 6 a.m., and they wouldn’t return home until 4 or 4:30 p.m. Mining was dangerous, dirty work. Miners used dynamite, as well as heavy picks, to break coal loose from the coal veins. When the siren blew, it was a sign that a miner was in trouble, or there had been a cave-in. “I can remember the whistle blowing in succession to let people know there had been an accident,” noted Angelo Stefani, whose uncle was killed in a mining accident. “I can also vividly member women coming out of their homes to see what happened. They were hysterical.” Miner working at the Shuler Coal Mine, Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Life in Waukee's coal mining community The Shuler mining camp was home to Italians, Croatians and people of other ethnicities. Most families lived in small, simple houses with no running water, but they often raised chickens and tended enormous gardens where they grew a variety of vegetables. Work wasn’t always steady. Dallas County’s coal mines often closed in the summer, when demand for coal dropped off in the warmer months. Miners would often work for local farmers or do odd jobs around the community to help pay the bills. Some of the miners’ wives, especially those in Italian families, worked at local restaurants like Rosie’s and Alice’s Spaghettiland near Waukee to supplement the family’s income. Alice Nizzi, founder and owner of Alice's Spaghettiland, an Italian restaurant open from 1947 – 2004 in Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Alice Nizzi (1905–1997) opened Alice’s Spaghettiland in the Shuler mining community just north of Hickman Road in 1947. The restaurant’s waitresses were required to wear white, starched uniforms. Alice’s became a destination and Waukee-area institution for decades until it closed in 2004. The Waukee Area Historical Society hosted a fundraising dinner in the spring of 2014 featuring Alice’s spaghetti and Italian salad. Hundreds of people now attend this fun event, which has been held each April for the past few years. Remembering the grape trainsFor Italian families in the Shuler mining camp, one of the highlights of the year was the arrival of the annual trainload of grapes for making homemade wine. “Excitement spread throughout the camp when the train arrived, and most of the people from the mining camp came to help unload the box cars,” said Gilbert Andreini, whose memories are recorded at the coal mining museum at the Waukee Public Library. “It was like a celebration.” The end of an era By the time the Shuler mine closed in 1949, Iowans began looking to energy sources other than coal for home use, such as electricity, natural gas and heating oil. In addition, the railroads were converting from steam to diesel engines, reducing the need of coal for locomotives. While Dallas County’s coal mines have vanished into history, those who grew up in the mining camps will never forget how these areas grew into close-knit communities. Everyone knew everyone else and helped each other out, recalled Bruno Andreini. “I’m very proud of those times. Anyone from that community is like a brother or sister to me. Even though we were poor, we had things that were far more valuable than money.” If you’d like to meet Darcy and hear more of her stories, she will be speaking at Hotel Pattee on September 11th, from 7 – 9 pm as part of Hometown Heritage’s fall programming series. For more information on this, please visit our website: www.hometownheritage.org/exhibits-and-events.html You can also learn more about Darcy on her website (www.darcymaulsby.com), and her book is available for pre-order on Amazon. Next week, tune in for a guest post written by author Rachelle Chase, who will continue our series on coal mining in Iowa with a post on the coal mining town of Buxton, an early Monroe county town whose population was racially integrated at a time when Jim Crow laws and segregation between African Americans and Caucasians were more common throughout the United States.

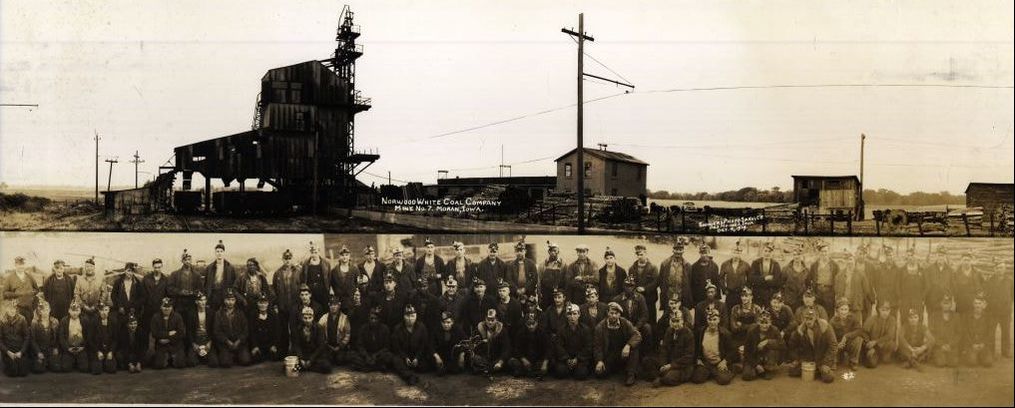

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! I am particularly excited for this week’s post, as it marks the first in a 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa. I hope you enjoy! Norwood-White #7 Coal Mine and employees on October 4, 1939, near Moran, IA. This photo was taken about a year before the mine closed. If you recognize a miner, please comment below or send the name to [email protected]. As with many other small towns in Iowa, Perry owes part of its origins to coal mining. By 1895, Iowa had 342 coal mines that employed over 6000 miners. Thirty years later, at the height of coal mining, twice as many people were employed as miners, with coal production steadily declining in the years after. The coal industry attracted many immigrants to Iowa. One of the interviews in Hometown Heritage’s collection is with a former miner who worked near Moran, which is a largely abandoned mining community south of Woodward that today consists of only a few remaining houses. He describes a culturally and ethnically diverse group of miners at Moran – roughly 25% Northern European (Irish, English, Welsh), 25% Eastern European (Yugoslavian and Czech), 25% Italian, and 25% African American. The multicultural nature of the workforce was acknowledged by the unions, who published the United Mine Workers Journal in English, Italian, and Slovakian in 1917. This publication was important for miners, as it included information on where work could be found and places to avoid due to strikes or overcrowding, as well as obituaries, cartoons, and even poetry. Life in the mines was hard work. Dangerous gases were a problem, as well as collapses and accidents. Physical injuries, such as hernias, were also common. Former miners recall workers, especially immigrants, being cheated by mining companies. In spite of these dangers, Dorothy Schwieder, who interviewed former Italian-American miners for her 1982 paper in The Annals of Iowa, suggested that some immigrants preferred working in the mines over factories. Down in the mines, they could work more independently and with less supervision, rather than working in a factory with a supervisor standing right over their shoulder. Many miners started working when they were teenagers and some as young as 9 years old. Older miners were often assisted by younger brothers or sons, which allowed the younger boys and men to learn the trade. The extra hands also benefited the older miners, who were able to produce more coal and increase their paychecks, since miners were often paid by the cart-load of coal. Miners generally made between $5.50 – 7.50 per day, but as with most people, they saw these wages fall during the Depression years. While miners often worked 8 hours a day – eating their lunches far below ground – their days were considerably longer. One former miner remembers leaving his house at 6 am, changing clothes at the camp wash house, waiting and riding into the mines together with other miners, working 8 hours, waiting and riding back out, returning to the wash house for a bath and change of clothes, and getting home around 9 pm. Iowa coal wasn’t well known for its favorable properties. B.P. Fleming, a professor who taught at the University of Iowa, wrote a paper in 1927 which listed its negative attributes. Iowa coal has high ash and iron content, which makes it less efficient to burn. Our coal also has a high moisture level, which made it difficult to sell. If the coal was dry, it crumbled easily, which led to the suggestion that coal be stored underwater. But if the coal was fresh out of the ground (or water), it weighed extra because of the absorbed water, resulting in unhappy buyers. Perhaps the biggest problem was that Iowa coal also had a high sulfur content, which made it smell when burnt and also introduced the possibility of spontaneous combustion. Fleming noted that “it is no uncommon thing to see a carload of Iowa coal come into the yards on fire.” But Iowa coal was not necessarily worse than the poorly graded coal from other states, so it was used locally in houses or industrial plants where people would put up with its poorer qualities in exchange for its lower price. As a result of this local use, however, mines often shut down in the summer – when Iowan’s needed less coal – so many miners found themselves unemployed and looking for temporary work. Location of the Norwood-White Coal Mine #7 near Moran, IA. The diagonal line going through the image is Highway 141, between Woodward and R22, and today, commuters drive over this abandoned mine on their way to Des Moines. Source: https://programs.iowadnr.gov/maps//coalmines/# The Norwood-White Mine #7, located near Moran, was in operation from 1919 – 1940 and employed around 250 miners. While not the largest mine in Iowa, it was 340 acres, consisted of two levels, and had a shaft depth of 205 ft. It was first opened in 1917, but production was halted when miners encountered an underground lake. One former miner remembers divers exploring the lake to see what was down there. Eventually, the Norwood-White company put a cement shaft through this underground body of water, allowing the miners to access the coal below. The Moran mine was closed in 1940 due to an underground fire. While valiant efforts were put forth to contain the blaze – one miner remembers a Woodward fire truck being driven into the mine to try to put it out – the fire was so hot that it burnt the slate on the mine roof. The mine, and some equipment (including tools that the miners paid for themselves), had to be abandoned. The Norwood-White Mine #7 had a fairly long life, since mines most were generally open for only 10 years. As a result, the camps and communities in which miners lived – places which contained housing, schools, taverns, restaurants, and stores – could also be short lived, as the miners moved on if other work was not close by. These ghost towns were often quickly dismantled and reclaimed by nature, with little trace of the bustling community that once was. Former site of Norwood-White Mine #3, Moran, IA, now farm ground. Next week, tune in for a guest post written by author and Dallas County historian Darcy Maulsby, who will discuss coal mining in Dallas County, including mines located in Waukee, Van Meter, and Woodward/Granger! In the meantime, below are just a few of the local Iowa museums that have great displays on coal mines:

Hello Readers!

We all know that Perry used to be a small town, built up around the railroad. Many towns sprang up around the tracks of the railroad, are plenty of them survived until today. However, did you know that there used to be another town quite close to Perry, and that its name was Angus? Angus was a coal-mining town that was about four miles northwest of Perry. It served as a terminal for the M. & St. L. Railroad, which was the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway. Now Angus used to be a thriving little town in the late 1800s. From what I have heard, it grew rapidly, even to the point where it used to be a bigger town than Perry (in the 1800s). A lot of this growth centered on the coal mine, as you may have guessed which I believe was the Mc Elheney Strip Mine. Of course, the entire town was not just about the mine. For example, one part of the town was called “Whisky Row”. All of the bars were in this part of town, and there are plenty of fun stories involved with it. My favorite that I have heard is about the law enforcement around these bars. Apparently Angus was a town that sat on the line between two counties, and Whiskey Row was right were this line was located. According to the stories, if someone got into trouble with the law at the bar, there was an easy way to get out of trouble. They could simply step to the other side of the bar, since it was in a different county, and had different jurisdiction! Now I am sure this did not work exactly as it sounds, but it is a fun little story. Unfortunately, Angus was not to last. By the early 1920s, the town had started to die out. The reason why it started to die out it is simple: the mines started to close. Without the mines, Angus could not support itself, and many of the people moved to Perry. Now there is not much left to Angus, but there is a plaque marking its location. If you have time, do not hesitate to go look at the plaque, or come by Hometown Heritage to see some of the photos. We have a lot more photos than just what I have put here! |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

All Rights Reserved, Fullhart Carnegie Charitable Trust, 2014-2023

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed