|

I had a group of 5th grade students here yesterday at the Carnegie Library Museum. They were using the courtroom downstairs to put the Big Bad Wolf on trial. He was found guilty, in case you were wondering. Anyway, it got me thinking about kids in Perry throughout the years. My kids want to spend most of their time playing video games or watching YouTube, but that obviously wasn’t the case with kids in the past. I was at the local coffee shop, Perry Perk, this morning and asked a couple of guys that grew up here in town what they did for fun as kids. The answers weren’t really surprising, but it led to a fun conversation.

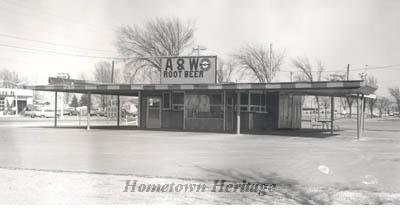

One of the guys talked about how he grew up out in the country and his parents would bring him into town in the summer and drop him off at the pool over at Pattee Park. It seems there were always friends there to mess around with. When he’d get bored with the pool, there were always ball games going on at the diamonds nearby. They mentioned the row of penny candy at Ben Franklin, and that you could get 2 or 3 pieces for a penny. The movie theater had Wednesday matinees, so they’d spend a dime, or so, on candy and sneak it into the theater. I guess some things don’t change. As they got older, they remember “scooping the loop” (we called it cruising in my hometown) down to A&W and back. Apparently there were a couple of drive-in diners, A&W and Dog ‘n Suds, and at least one drive-in theater. You couldn’t go wrong getting a cherry Coke or a Green River at one of the many soda fountains in town. A search for “soda fountain” in our photo archives netted 14 photos, many of which include pretty girls working at the counter. The guys also remember playing pool for a dime a game at Farnham Billiards. They said that Harold would rack up the balls for them. In researching for this article, I found the story of a guy talking about when he was a teen and his parents would give him a dollar to go get his haircut. If the line at the barber shop was too long, he’d go down the street and start playing pool, and before he knew it his dollar would be gone and he’d be on his way home trying to figure out how to explain his long hair to his parents. Technology and kids ideas of entertainment might change over the years, but it doesn’t seem like kids themselves have changed much at all.

0 Comments

Baseball season has just wrapped up with the Washington Nationals beating the Houston Astros to win their first World Series title ever. It reminds me of a baseball game played here in Perry back in 1922.

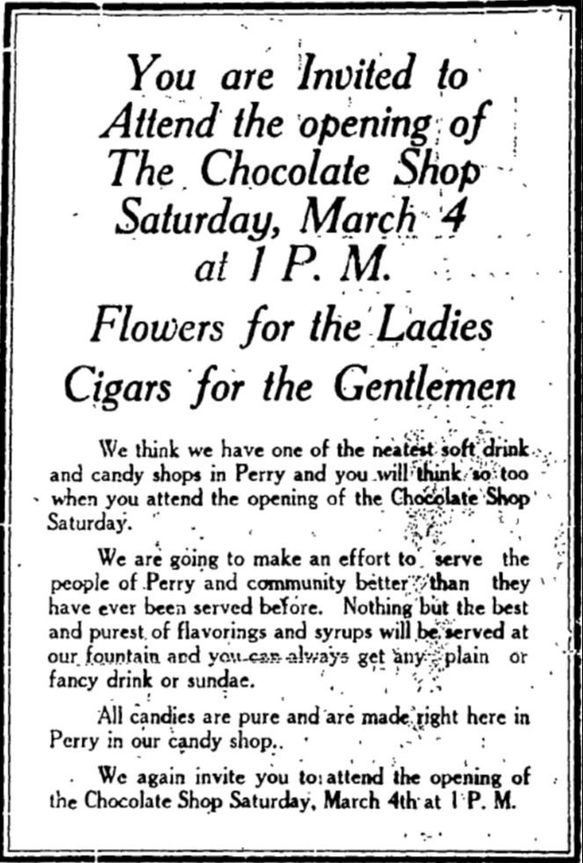

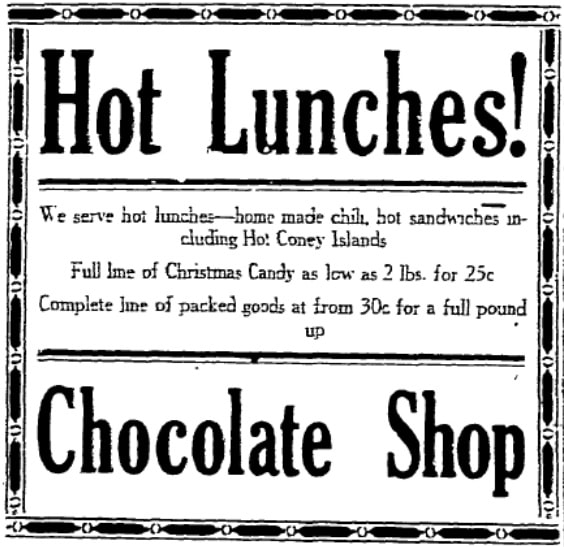

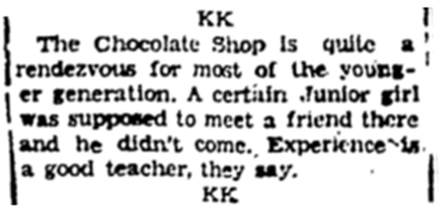

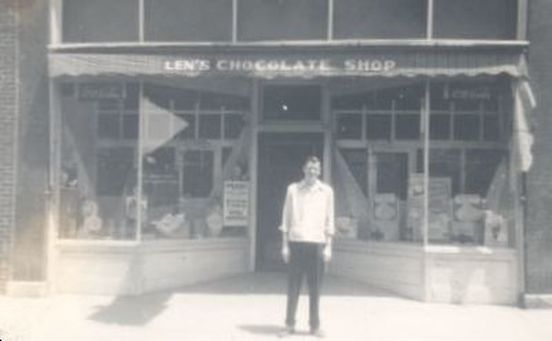

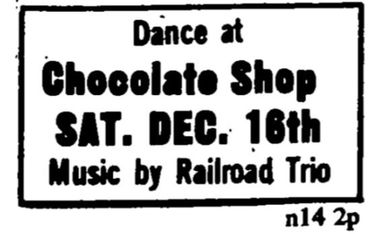

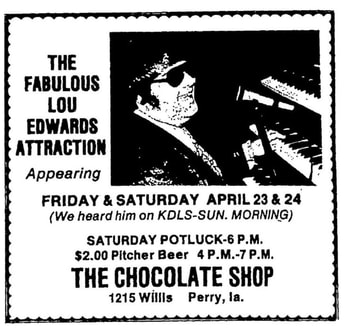

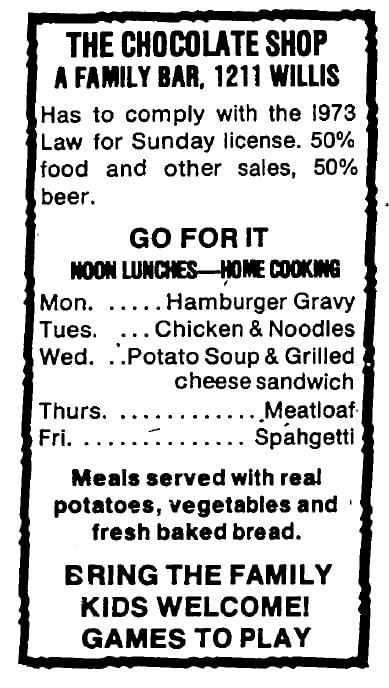

In October of 1922, Babe Ruth and a less popular but still very successful player in his own right, Bob Meusel, came to town to play an exhibition game. There was a lot of hype and excitement, as you can imagine, leading up to the event. The Perry branch of the American Legion had organized the event and hoped to make a tidy sum of cash off of ticket sales. Unfortunately, the day ended up being cold and dreary, and even though the rain mostly stopped an hour or so before the game began, the attendance was much lower than hoped. Ruth and Meusel ended up taking most of the profits home with them. I guess that’s what happens when you play a baseball game on Friday the 13th. The game was against Pella, and Meusel played for them while Ruth played for Perry. Meusel hit a homerun and Babe hit a couple of triples. You’d think “The Sultan of Swat” could have managed at least one homer, but apparently the outfield wasn’t enclosed by a fence, which enabled the outfielder to get to the ball and throw it back in before the lumbering Ruth could get past third base. I hadn’t realized until recently that the Ku Klux Klan was very active in Perry around that same time. I also didn’t know that the KKK was extremely anti-Catholic. Babe Ruth was Catholic and is said to have even visited St. Patrick’s School while in town. You would think given the fact that, according to a The Perry News article, a KKK grand master lived in town, there would have been protests and maybe even a cross burning. In reality, Babe Ruth coming to town was such a big deal that KKK members decided to forgo their prejudice for the day and instead sat in the stands and cheered for him and the hometeam along with everyone else. I guess that’s what happens when you play a baseball game in Perry. God bless America. Group of teens at Perry’s Chocolate Shop at 1220 2nd St, c. 1946. If you recognize a Chocolate Shop patron, please comment below or contact [email protected]. On March 4, 1922, Tom Angnos opened Perry’s Chocolate Shop at 1109 2nd St. Tom emigrated from Greece to the United States in 1914, and worked on the railroad before becoming a candy maker and moving to Perry. In the early 1920s, the Chocolate Shop was a candy, ice cream, and soda shop, selling fudge and caramels for 15-28 cents per lb. March 3, 1922 Perry Daily Chief ad for the grand opening of the Chocolate Shop at 1109 2nd St. In 1925, George Barbes became the manager, moved the Chocolate Shop to 1116 2nd St, and began selling lunches. December 14, 1927 Perry Daily Chief advertisement listing hot lunches and Christmas candy at the Chocolate Shop. The Chocolate Shop changed hands one more time, and survived a fire, before Al Kouri took over in November 1928. Kouri, an immigrant from Syria, came to the United States as a teenager in 1910. He had been awarded a prestigious high school education in France, but he didn’t like the school in Marseilles. With a group of friends, Kouri surprised his family by taking a ship to the United States instead of back to school. After sorting things out at Ellis Island, he moved to Des Moines, where he lived with an aunt and went to high school, before coming to Perry. Kouri was one of the longest running owners of the Chocolate Shop (1928 – 1946), and under his management, the Chocolate Shop began to sell beer (1933) and moved to its 1220 2nd St. location (1937). Once beer sales began, the Chocolate Shop was divided into two, with a jukebox, lunch counter, and ice cream in the front and the bar in the back. The shop continued to be popular with high schoolers, railroaders, ladies, businessmen, and just about everyone else in town. February 27, 1934 Komment Kolumn of the Perry High School Telital in the Perry Daily Chief. A teen criticizes a male friend for standing her up for their date at the Chocolate Shop. The Chocolate Shop was later owned by Leonard Sorenson around 1946 – 1948, and managed by Barney Sorensen and D.D. Lewiston, who later served as Perry’s mayor. Around this time, the Chocolate Shop was briefly called Len’s Chocolate Shop, and was open for the first time on Sunday afternoons and evenings (1948). Storefront of Len’s Chocolate Shop, c. 1946 – 1955. After changing hands once again, and surviving another fire, Carroll and Helen Jenkins took ownership in 1956, and managed the store until it closed in 1977. Under the Jenkins, in 1964 the Chocolate Shop received a permit that allowed public dancing, as long as a policeman was present, and the addition of live music and dances cemented the Chocolate Shop as the Saturday night place to be. The Chocolate Shop closed when the Jenkins lost their lease in 1977, but a painting of the Milwaukee railroad train that hung inside can still be seen at the Crooked Rail bar here in Perry. December 14, 1972 Perry Daily Chief ad for a Saturday Night dance at the Chocolate Shop. This was not the end, however, of the Chocolate Shop. On January 18, 1979, another bar called the Chocolate Shop opened at 1215 Willis Ave. Unlike its predecessor, this establishment never specialized in homemade candy but was mainly a bar, which offered drink specials on Wednesday nights, weekday noon lunches, live music, fun and games on Saturday nights, and advertised a family environment, particularly on Sundays, when, by law, only half of the bar’s sales could come from alcohol. The new Chocolate Shop moved once in 1982, to 1211 Willis Ave, before it too later closed. Thanks to Katie Edmondson, John Palmer, Larry Vodenik, and many others for sharing their Chocolate Shop memories and helping research this post. Please share your Chocolate Shop memories below, and for more, come see our exhibit on the Chocolate Shop at the Carnegie Library Museum, on display now through March 21, 2018.

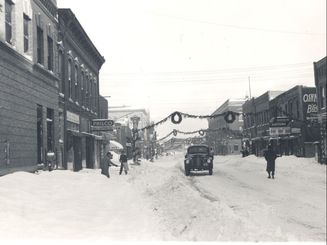

Christmas on 2nd Street, just north of Willis Ave, in Winter 1942 (left) and on December 15, 2017 (right). Welcome to the Christmas edition of the Hometown Heritage blog! Today, we’ll be taking a trip down memory lane, looking at some historic Christmas decorations as well as reminiscing about how Perry’s business district has changed over time. The photos above show the home of Perry’s Lighted Christmas Parade (2nd Street, just north of Willis) in 1942 and 2017. While we haven’t had any measurable snow yet this year, the 1942 photo shows Perry residents and businesses coping with a recent heavy snowfall. Festive garlands encircle 2nd Street’s light poles, while garlands and wreaths were suspended for several blocks over Perry’s commercial district. The 1942 photo also shows several businesses of the day. A Philco Hall Maytag Co. office is on the west side (left) of the street, where the Crisis Intervention & Advocacy Center is today, and a car dealership used to reside in today’s Josh Davis Memorial Plaza. Robinson’s Clothing can be seen on the east side (right) of the street, which had overcoats on sale for $14, $16, or $24. In the alley south of the store, part of a large painted advertisement for OshKosh B’Gosh can also be seen. Christmas on 2nd Street, just north of Lucinda St, in late Fall c. 1951 (left) and December 15, 2017 (right). On a rather warm day in late fall, likely in 1951, Perry residents set to decorating 2nd Street for Christmas. Once again, suspended garlands hung over the street, this time, adorned with large stars and bells. The date for this photo can be narrowed down by the movie on the Perry theater marque, Francis Goes to the Races. This picture, a sequel, was a black-and-white filmed comedy from Universal released in May 1951, which told the story of a talking mule and his owner who becomes entangled with the mob. The Perry Theater likely didn’t get this film right away, so it was showing later that year. A number of 1950’s businesses can also be seen in this photo. On the west side (left) of the street, Rosie’s Café served food where today’s Eye Care Associates is located, the Perry Gas Co. did business in 2017’s H&R Block building, and the Perry Daily Chief newspaper was housed on the west side of the street. In addition, one of Perry’s furniture stores – Bennett-McDaniel Furniture – can be seen between Rosie’s Café and the Perry Gas Co. On the other side of the street, a sandwich shop is located near the end of the block and a Sinclair Gasoline H-C sign is visible just past this. In the center of the photo toward the back, a car can also be seen stopped at the railroad crossing, waiting for the train to go by. Christmas at the Carnegie Library. Left: Librarian Marian Krohnke sits by the fire (c. 1953). Right: The Festival of Trees (December 15, 2017). The Carnegie Library also got into a festive spirit. The photo on the left, showing Librarian Marian Krohnke, dates to around 1953. While she isn’t sitting next to a roaring fire, the fireplace mantle displays a nativity scene.

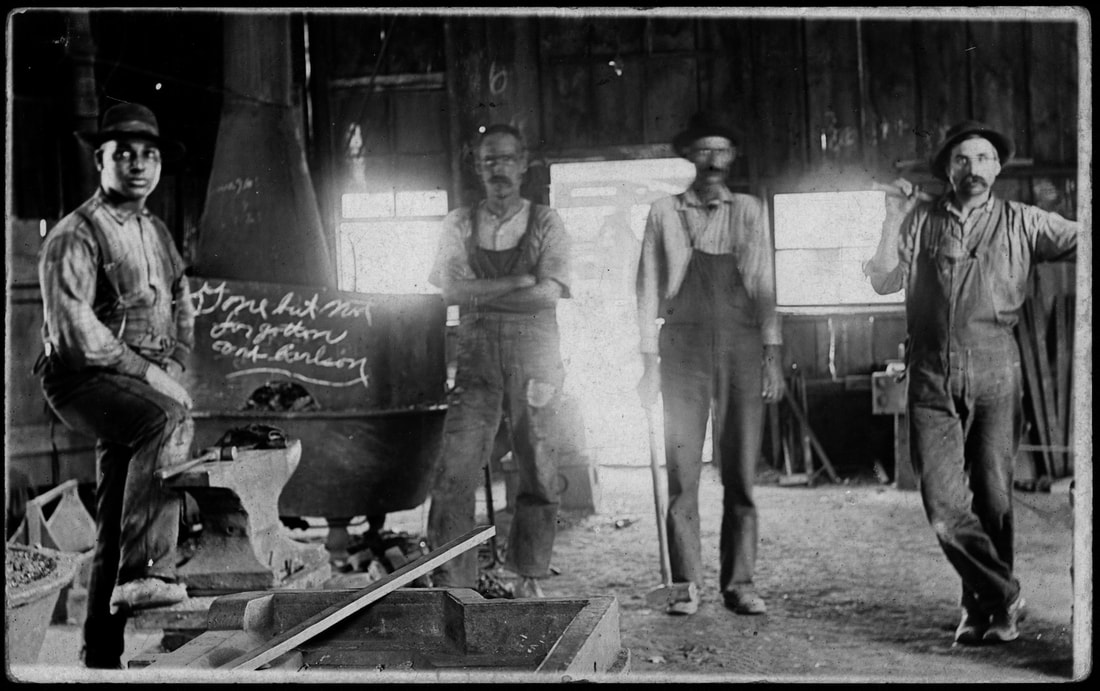

Today, the Carnegie Library Museum hosts the Festival of Trees. Carnegie volunteers Katie Schott and Laura Stebbins organize this annual event, in which local businesses, churches, and organizations set up festive displays, each vying for visitor votes in this fundraising and cheer-raising event. The photo on the right is just the tip of the iceberg that is the 39 (!) displays, which can be viewed through the end of this month (see the schedule below for holiday hours). Make sure to stop in and see this festive exhibit! We at Hometown Heritage would like to thank all of our wonderful volunteers, visitors, and supporters this year, and wish you and yours very happy holidays! Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! This week’s post marks the third and final post in our 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa (you can find the other posts here and here). This week’s post is by author Rachelle Chase. Even before moving to Iowa, the history of Buxton, Iowa, and its former residents fascinated Rachelle, and now that she has become an Iowa resident, she is determined to help share their story. Rachelle is the author of multiple fiction books and the non-fiction book, Lost Buxton. In 1900, Consolidation Coal Company established one of the most unique towns in Iowa: Buxton. Spanning 8,600 acres in Monroe County and 1,600 acres in Mahaska County, along with a population that grew to 5,000, Buxton became the largest unincorporated town in Iowa. Though the town itself was different from most other coal mining towns, Buxton is renowned for its large African American population. For the first 10 years, African Americans made up 55% of the population and remained the largest ethnic group until 1914. A Planned Town The typical mining town featured hastily constructed houses, a company store, a small school, a tavern, a union hall, and a church. Buxton was not “typical.” Buxton residents enjoyed 1-1/2 story houses which were maintained by the company, a company store that rivaled department stores, three two-story schoolhouses, a two-story high school, a three-story YMCA, and more than 10 churches. According the September 18, 1903 edition of the Iowa State Bystander, Superintendent Ben C. Buxton “designed and superintended the laying out of the town, the plans and construction of the buildings, the location and equipment of the mines, the water supply, the drainage and all the many interesting details ...” Buxton, Iowa, looking north. “Boy’s Y” (rectangular white building, left), YMCA (far left), W.H. Wells Company Store (center). The company store burned down in 1911 and was replaced with a brick building and renamed Monroe Mercantile Company Store. Courtesy: Michael W. Lemberger. A Prosperous Town As mentioned in previous posts, mining was often seasonal, which resulted in a reduced demand for coal in the warmer months. This was not the case in Buxton. Since Consolidation Coal Company was owned by the Chicago & North Western Railroad and trains required a constant supply of coal, men in Buxton worked year-round, earning $40-$100 every two weeks. “The miners received excellent pay according to the economy at that time,” said Reuben Gaines Jr., a successful African American businessman in Buxton, in an undated memoir. “In any event or manner the money flowed freely.” There was no shortage of ways residents in Buxton could spend money. They could shop at more than 40 independent businesses, plus the company store. “You could buy anything in that company store, from a diaper pin to a coffin,” said Kietzman. “The company had its own morticians and own mortuary. They had a shoe department, shoe repair department, furniture, hardware, groceries, cooking ware, clothing, and yard goods. The company store had a bank in it, the company office, a soda fountain where they served lunches.” A Racially Integrated Town Former residents—both black and white—agreed that Buxton was integrated and that any segregation that did exist, such as separate churches, was by choice. The company awarded housing on a first-come, first-served basis; 16 of the 85 company store clerks were black; black men and white men worked in the mines in neighboring “rooms”; black children and white children were taught by black and white teachers; and residents attended public events—baseball games, movies, parades, and picnics—sitting or standing wherever they desired. Believed to be blacksmith’s shop in Buxton, Iowa. Courtesy: State Historical Society of Iowa Residents also remembered interracial marriages. “There were a lot of interracial marriages down there...” said Oliver Burkett, an African American resident. “There was Charlie King, he was a black man, he married a white woman. Hobe Armstrong, he was a black man and he married a white woman. George Morrison, he was married to a white woman.” Carl Kietzman, previously quoted, was married to an African American woman. African Americans Thrived In addition to miners, there were many African American professionals and business owners in Buxton. African American professionals included doctors, lawyers, a dentist, pharmacists, constables, teachers, commercial and rental property owners, an insurance agent, company store clerks and at least one manager, a bank manager, a cigar maker, a postmaster, a mine engineer, two justices of the peace, barbers, a tailor, and many entrepreneurs. Black-owned businesses included hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, confectionaries, a bakery, drug stores, pool halls, dance halls, a music store, a photography and printing business, a meat market or two, millinery shops, and at least four newspapers. The End of Buxton By 1918, the mines near Buxton were almost completely played out and the company had moved operations to Consol, located 18 miles southwest of Buxton, and Bucknell/Haydock. By 1922, Buxton was a ghost town. Miners and their families had moved to other cities in Iowa and beyond in search of work or had moved to the company’s new towns. But by 1927, the continuing decline in coal demand and the negative perception of Iowa coal, plus labor problems, resulted in the shutdown of remaining mines. Consol and Bucknell/Haydock, like Buxton, were gone. The company store’s stone warehouse, the largest remaining structure in Buxton, Iowa in 2016. Source: Rachelle Chase For many African American residents, leaving Buxton was like stepping back in time. Jim Crow laws, segregation, extreme racism, and menial jobs awaited them, leaving many feeling like Susie Robinson. “There’s no place that’s ever going to be like Buxton,” said Robinson. “That’s the best place that I’ve ever been, Buxton.” If you would like to learn more about Buxton, Rachelle’s book, which uses rare photographs and quotes from former residents to tell its unique history, can be found on Amazon. You can also learn more about Rachelle and her books on her webpage.

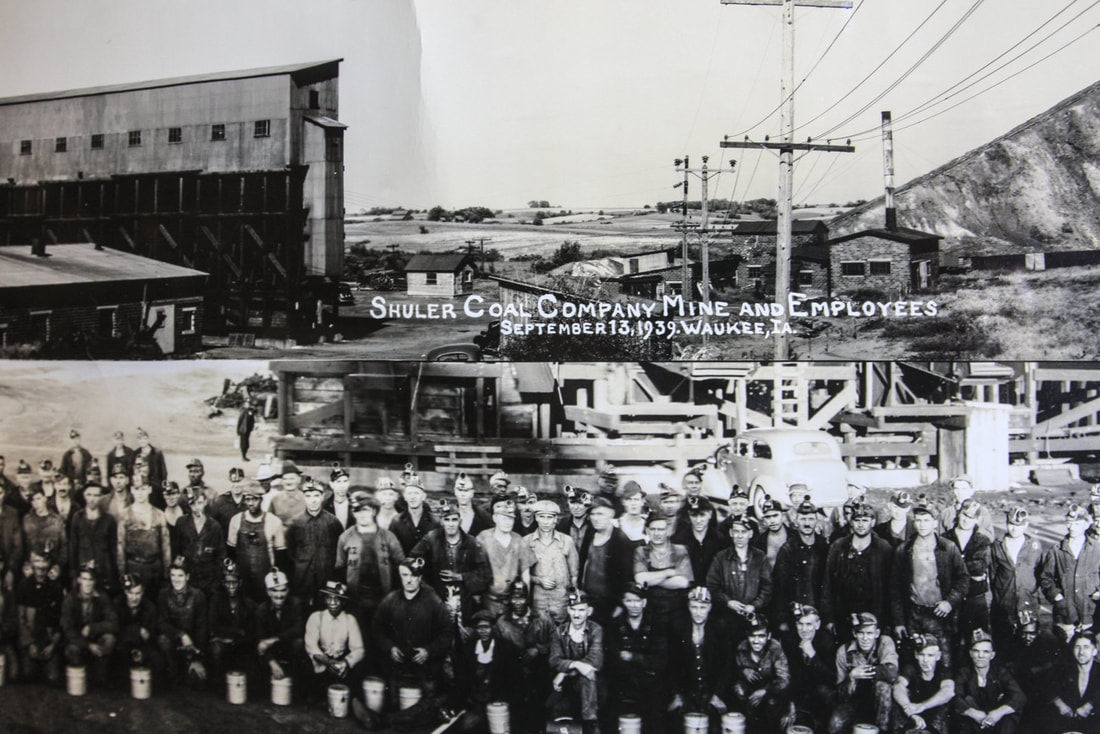

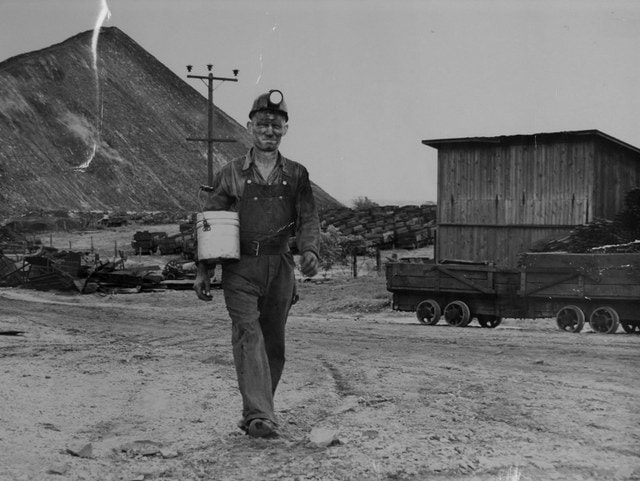

I hope you’ve enjoyed our mining series as much as I have, and many thanks to our guest authors Darcy and Rachelle! Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! This week’s post marks the second in a 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa (you can find the first post here). This week’s post is by author Darcy Maulsby. Darcy is an Iowa native, former Dallas county resident, and author of three history books, including the soon-to-be-published Dallas County. Enjoy! There was a time when Dallas County was one of the most important coal-mining counties in Iowa. While this way of life vanished decades ago, the memories live on, from the Hotel Pattee in Perry to the Waukee Public Library to the many descendants of mining families who still live in the area. From Moran to Woodward to Waukee, Dallas County thrived with the increased demand a century ago for coal to power train locomotives and heat businesses and homes. Coal was a relatively cheap, plentiful energy source. With ample supplies of coal, Dallas County became a land of opportunity for immigrant miners from Europe and beyond. Coal mining started in the Van Meter area as early as the 1870s. By the early 1900s, coal was discovered in Des Moines Township east of Woodward, leading to the creation of the Scandia and Phildia mining settlements. After the Phildia mine was abandoned in 1915 and the Scandia mine closed in 1921, miners moved on to the Moran mine, which opened in 1917 west of Woodward. You might remember Moran from last week’s post. It's not on most maps today, but there was a time when Moran was a bit of a boom town. The Angus & Moran Room at the Hotel Pattee in Perry recalls the history of Moran and Angus, a once-thriving mining town east of Perry that once boasted thousands but now has only a handful of residents. Shuler Coal Mine and employees on September 13, 1939, in Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Living with danger On the opposite side of Dallas County, coal mining also transformed the Waukee area in the early twentieth century. The Harris Mine opened on September 20, 1920, just two and a half miles northeast of Hickman Road in Waukee. By 1921, the Shuler Coal Company of Davenport, Iowa opened a coal mine on Alice’s Road, one mile east of the Harris Mine. At its peak production, the mine employed more than 450 men. The Shuler Mine became one of the largest producers of coal in Iowa, and it had one of the deepest mine shafts--387 feet deep. The mine produced coal for Iowa State University, as well as for local railroads, businesses and homes. The miners worked in the Shuler mine with the help of more than 30 mules, bringing up hundreds of tons of coal per day and millions of tons of coal over the mine’s 28 years of operation. The miners’ work day often started at 6 a.m., and they wouldn’t return home until 4 or 4:30 p.m. Mining was dangerous, dirty work. Miners used dynamite, as well as heavy picks, to break coal loose from the coal veins. When the siren blew, it was a sign that a miner was in trouble, or there had been a cave-in. “I can remember the whistle blowing in succession to let people know there had been an accident,” noted Angelo Stefani, whose uncle was killed in a mining accident. “I can also vividly member women coming out of their homes to see what happened. They were hysterical.” Miner working at the Shuler Coal Mine, Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Life in Waukee's coal mining community The Shuler mining camp was home to Italians, Croatians and people of other ethnicities. Most families lived in small, simple houses with no running water, but they often raised chickens and tended enormous gardens where they grew a variety of vegetables. Work wasn’t always steady. Dallas County’s coal mines often closed in the summer, when demand for coal dropped off in the warmer months. Miners would often work for local farmers or do odd jobs around the community to help pay the bills. Some of the miners’ wives, especially those in Italian families, worked at local restaurants like Rosie’s and Alice’s Spaghettiland near Waukee to supplement the family’s income. Alice Nizzi, founder and owner of Alice's Spaghettiland, an Italian restaurant open from 1947 – 2004 in Waukee, IA. Source: Waukee Area Historical Society Alice Nizzi (1905–1997) opened Alice’s Spaghettiland in the Shuler mining community just north of Hickman Road in 1947. The restaurant’s waitresses were required to wear white, starched uniforms. Alice’s became a destination and Waukee-area institution for decades until it closed in 2004. The Waukee Area Historical Society hosted a fundraising dinner in the spring of 2014 featuring Alice’s spaghetti and Italian salad. Hundreds of people now attend this fun event, which has been held each April for the past few years. Remembering the grape trainsFor Italian families in the Shuler mining camp, one of the highlights of the year was the arrival of the annual trainload of grapes for making homemade wine. “Excitement spread throughout the camp when the train arrived, and most of the people from the mining camp came to help unload the box cars,” said Gilbert Andreini, whose memories are recorded at the coal mining museum at the Waukee Public Library. “It was like a celebration.” The end of an era By the time the Shuler mine closed in 1949, Iowans began looking to energy sources other than coal for home use, such as electricity, natural gas and heating oil. In addition, the railroads were converting from steam to diesel engines, reducing the need of coal for locomotives. While Dallas County’s coal mines have vanished into history, those who grew up in the mining camps will never forget how these areas grew into close-knit communities. Everyone knew everyone else and helped each other out, recalled Bruno Andreini. “I’m very proud of those times. Anyone from that community is like a brother or sister to me. Even though we were poor, we had things that were far more valuable than money.” If you’d like to meet Darcy and hear more of her stories, she will be speaking at Hotel Pattee on September 11th, from 7 – 9 pm as part of Hometown Heritage’s fall programming series. For more information on this, please visit our website: www.hometownheritage.org/exhibits-and-events.html You can also learn more about Darcy on her website (www.darcymaulsby.com), and her book is available for pre-order on Amazon. Next week, tune in for a guest post written by author Rachelle Chase, who will continue our series on coal mining in Iowa with a post on the coal mining town of Buxton, an early Monroe county town whose population was racially integrated at a time when Jim Crow laws and segregation between African Americans and Caucasians were more common throughout the United States.

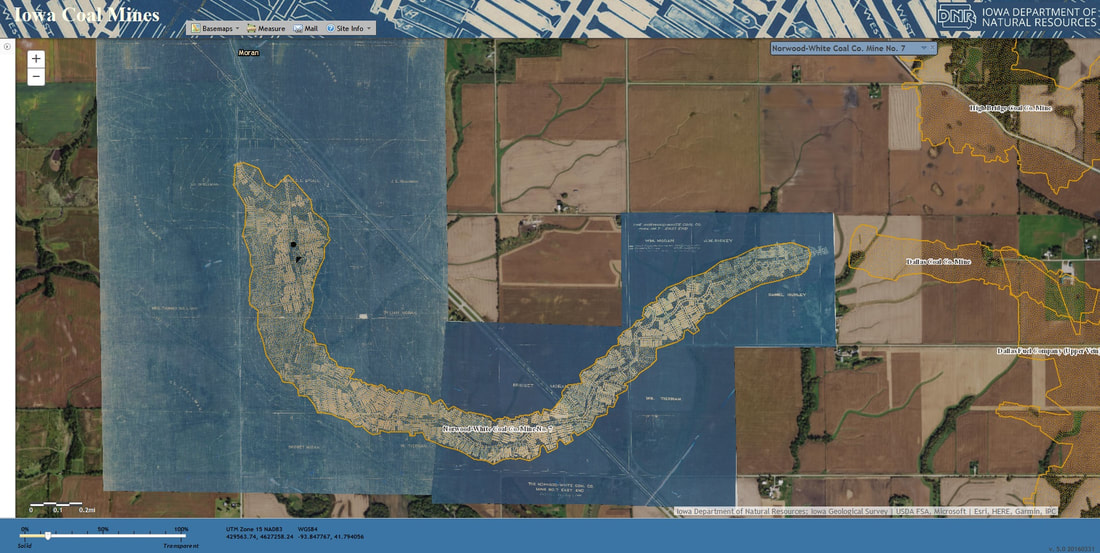

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! I am particularly excited for this week’s post, as it marks the first in a 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa. I hope you enjoy! Norwood-White #7 Coal Mine and employees on October 4, 1939, near Moran, IA. This photo was taken about a year before the mine closed. If you recognize a miner, please comment below or send the name to [email protected]. As with many other small towns in Iowa, Perry owes part of its origins to coal mining. By 1895, Iowa had 342 coal mines that employed over 6000 miners. Thirty years later, at the height of coal mining, twice as many people were employed as miners, with coal production steadily declining in the years after. The coal industry attracted many immigrants to Iowa. One of the interviews in Hometown Heritage’s collection is with a former miner who worked near Moran, which is a largely abandoned mining community south of Woodward that today consists of only a few remaining houses. He describes a culturally and ethnically diverse group of miners at Moran – roughly 25% Northern European (Irish, English, Welsh), 25% Eastern European (Yugoslavian and Czech), 25% Italian, and 25% African American. The multicultural nature of the workforce was acknowledged by the unions, who published the United Mine Workers Journal in English, Italian, and Slovakian in 1917. This publication was important for miners, as it included information on where work could be found and places to avoid due to strikes or overcrowding, as well as obituaries, cartoons, and even poetry. Life in the mines was hard work. Dangerous gases were a problem, as well as collapses and accidents. Physical injuries, such as hernias, were also common. Former miners recall workers, especially immigrants, being cheated by mining companies. In spite of these dangers, Dorothy Schwieder, who interviewed former Italian-American miners for her 1982 paper in The Annals of Iowa, suggested that some immigrants preferred working in the mines over factories. Down in the mines, they could work more independently and with less supervision, rather than working in a factory with a supervisor standing right over their shoulder. Many miners started working when they were teenagers and some as young as 9 years old. Older miners were often assisted by younger brothers or sons, which allowed the younger boys and men to learn the trade. The extra hands also benefited the older miners, who were able to produce more coal and increase their paychecks, since miners were often paid by the cart-load of coal. Miners generally made between $5.50 – 7.50 per day, but as with most people, they saw these wages fall during the Depression years. While miners often worked 8 hours a day – eating their lunches far below ground – their days were considerably longer. One former miner remembers leaving his house at 6 am, changing clothes at the camp wash house, waiting and riding into the mines together with other miners, working 8 hours, waiting and riding back out, returning to the wash house for a bath and change of clothes, and getting home around 9 pm. Iowa coal wasn’t well known for its favorable properties. B.P. Fleming, a professor who taught at the University of Iowa, wrote a paper in 1927 which listed its negative attributes. Iowa coal has high ash and iron content, which makes it less efficient to burn. Our coal also has a high moisture level, which made it difficult to sell. If the coal was dry, it crumbled easily, which led to the suggestion that coal be stored underwater. But if the coal was fresh out of the ground (or water), it weighed extra because of the absorbed water, resulting in unhappy buyers. Perhaps the biggest problem was that Iowa coal also had a high sulfur content, which made it smell when burnt and also introduced the possibility of spontaneous combustion. Fleming noted that “it is no uncommon thing to see a carload of Iowa coal come into the yards on fire.” But Iowa coal was not necessarily worse than the poorly graded coal from other states, so it was used locally in houses or industrial plants where people would put up with its poorer qualities in exchange for its lower price. As a result of this local use, however, mines often shut down in the summer – when Iowan’s needed less coal – so many miners found themselves unemployed and looking for temporary work. Location of the Norwood-White Coal Mine #7 near Moran, IA. The diagonal line going through the image is Highway 141, between Woodward and R22, and today, commuters drive over this abandoned mine on their way to Des Moines. Source: https://programs.iowadnr.gov/maps//coalmines/# The Norwood-White Mine #7, located near Moran, was in operation from 1919 – 1940 and employed around 250 miners. While not the largest mine in Iowa, it was 340 acres, consisted of two levels, and had a shaft depth of 205 ft. It was first opened in 1917, but production was halted when miners encountered an underground lake. One former miner remembers divers exploring the lake to see what was down there. Eventually, the Norwood-White company put a cement shaft through this underground body of water, allowing the miners to access the coal below. The Moran mine was closed in 1940 due to an underground fire. While valiant efforts were put forth to contain the blaze – one miner remembers a Woodward fire truck being driven into the mine to try to put it out – the fire was so hot that it burnt the slate on the mine roof. The mine, and some equipment (including tools that the miners paid for themselves), had to be abandoned. The Norwood-White Mine #7 had a fairly long life, since mines most were generally open for only 10 years. As a result, the camps and communities in which miners lived – places which contained housing, schools, taverns, restaurants, and stores – could also be short lived, as the miners moved on if other work was not close by. These ghost towns were often quickly dismantled and reclaimed by nature, with little trace of the bustling community that once was. Former site of Norwood-White Mine #3, Moran, IA, now farm ground. Next week, tune in for a guest post written by author and Dallas County historian Darcy Maulsby, who will discuss coal mining in Dallas County, including mines located in Waukee, Van Meter, and Woodward/Granger! In the meantime, below are just a few of the local Iowa museums that have great displays on coal mines:

Scouts at Camp Mitigwa, north of Woodward, IA in 1958. If you recognize a scout, please comment below or email me at [email protected]. Welcome back, dear readers, to the Hometown Heritage blog! With the heat of summer comes the time honored tradition of summer camps. Scouting has a rich history in the Midwest. Boy scouts have been in Iowa since at least 1911, and Camp Mitigwa – the local scout camp located north of Woodward – was established in 1923. Prior to this, boy scouts attended camps at the Ledges and in a temporary site north of Adel. In the 1920s, teenagers were the most common age group involved with Boy Scouts, with most scouts aged between 12 – 13 years. Scouting attracted boys and young men from families of a variety of income levels – from upper class to working class. The early goals of the Boy Scouts were much the same as today: to develop character, citizenship, and mental and physical fitness. Scouting encouraged boys to pursue their own interests and learn by doing. Scouting also prepared them for adult life, which in the 1910s – 1920s, could include jobs in factories or politics. Cub Scouts, scouts who were younger than 12 years, officially became part of the Boy Scouts in 1930, though earlier versions of programing for younger boys had existed since 1918. Among their many other activities, Boy Scouts early on were involved in presidential inaugurations, and during the World Wars, scouts sold war bonds and stamps, and collected aluminum, rubber, and wastepaper during WWII. The Pinewood Derby – in which scouts build and race their own wooden cars -- officially became a Boy Scout event in 1955, and by 1958, when the photo above was taken, almost 5 million boys were enrolled in Boy Scouts and Cub Scouts nationally. Dorothy Vodenik, circa 1948, giving the Girl Scout salute. The Girl Scouts also have a deep history, dating back in America to 1912. Early on, the organization emphasized self-reliance, patriotism, service, inclusiveness, and the outdoors, and today encourages confidence, character, and courage in girls. From the beginning – when the Girl Scouts were just a small troop of 18 girls – the organization attracted young women from a variety of cultures, ethnicities, and income levels, and an early goal of the Girl Scouts was to help immigrant girls become accustomed to life in America. During the Depression, Girl Scouts collected food and clothing for those in need, and during WWII, girls collected scrap metal and ran Farm Aid projects. Iowa had several Girl Scout camps that date back to at least the 1920s (Camp of the Hills, Sioux City; Camp Cardinal and Camp Whip-Poor-Will, Iowa City; Camp Crystal, Le Mars), and some Iowa troops even used Camp Mitigwa from the 1930s – 1950s. Construction began on Camp Sacajawea – the local scout camp located north of Boone – in 1947, and prior to this, local scouts may have stayed at the Ledges or other campsites. The sale of cookies as a fundraiser for troop activities dates back to 1917, with girls and their mothers baking cookies in their own homes. Cookie recipes were published in Girl Scout magazines as early as 1922 (for this recipe, see below!), and in the 1930s, the Girl Scouts began to sell commercially baked cookies. Current favorites Thin Mints and Shortbread cookies were first sold in 1951, and Peanut Butter Sandwich cookies arrived in 1966. 1922 Girl Scout Cookie Recipe, published in the July 1922 issue of The American Girl by Florence E. Neil, a Girl Scout Director in Chicago, IL. (Source: http://www.girlscouts.org/en/cookies/all-about-cookies/Cookie-History.html) For more on Boy and Girl Scouts history, the official websites of the Iowa councils have great information on the history pages. Also, check out the Vintage Girl Scout Online Museum, which has a page that collects newspaper articles on Iowa Girl Scout camps (http://www.vintagegirlscout.com/campIA.html). Hi Everyone! Welcome (and welcome back!) to the Hometown Heritage blog.

My name is Alissa Whitmore, and I am pleased to join the staff here at Hometown Heritage in Perry, Iowa. This week, I wanted to introduce myself, as well as let you know about a few of the projects that I will be working on this summer. I have lived in Perry the majority of my life, having moved to town with my family in 1989. I graduated from Perry High School in 2002, and then went to college at the University of Iowa. I have always loved history, so I took classes in prehistory (which is just history before written records), the Greeks and Romans, and archaeology. I have been fortunate to be part of excavations right here in Iowa, as well as in Italy and the Netherlands. In graduate school, I studied at museums, archives, and archaeological sites at Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy, as well as in Germany, Switzerland, England, and Wales in preparation for writing my dissertation on the Romans to obtain my Ph.D. During and after grad school, I taught at the University of Iowa and Des Moines Area Community College before deciding that I wanted to pursue a career in museums. I love museums for the same reasons that you do – the atmosphere of past places, the stories that objects and photos can tell, and the desire to know who and what came before us. I’ll be splitting my time between Hometown Heritage in Perry and the State Historical Museum in Des Moines, as well as continuing to do some local archaeology in Iowa. In the coming weeks at Hometown Heritage, I’ll be making some changes to our exhibits, revamping our online searchable photo collection, connecting with local schools to offer educational outreach to students (Homeschool parents! Please stop by or send me an email ([email protected]), and we can talk about what Hometown Heritage can offer your students!), and planning some great events for later this summer (including an event with an amazing Iowa author who has an upcoming book on Dallas County history!). And for those with an interest in genealogy, we have computers with access to Ancestry.com and digitized Perry newspapers dating back to 1874. Starting in July, I’ll be here at Hometown Heritage on Wednesdays – Fridays, 9:00 am – 5:00 pm, so please stop in to say hello, see some of the changes, and hear more about what Hometown Heritage and our unique collections can offer you! Hello readers and welcome back to the Hometown Heritage Blog!

Today I have some news for all of you: this will be my last blog post for Hometown Heritage. Tomorrow, June 15th, will be my last day here. If you want to come and see me at the Carnegie, then tomorrow is the day to do it! I am starting a new chapter in my life and will be applying to graduate school to get a degree in Museum Studies. My hope is one day to work in a Museum with its collection. Hometown Heritage has taught me many valuable lessons and I am very thankful for my time here. I also want to thank all of you, readers, for coming back every week to read these posts! I am glad that I was able to entertain you every week with fun stories and pictures from our collection. However, just because I am leaving does not mean that the blog will stop. Our newest hire here at Hometown Heritage will continue the blog, and more new and interesting stories and pictures from our collection will continue to be told. So again, thank you for coming back each week during these two years, and come back soon for another Hometown Heritage blog! P.S. This is Bill Clark with my own addition to this week’s blog. We are grateful for the many valuable contributions that Jared has made in his time with us at Hometown Heritage. His future is bright and I am confident of his success going forward. We are grateful to have played a small part in his career development. His blogs will be a “tough act” to follow for anyone. Best regards Jared!! Bill Clark and all the Trustee Board |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

All Rights Reserved, Fullhart Carnegie Charitable Trust, 2014-2023

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed