|

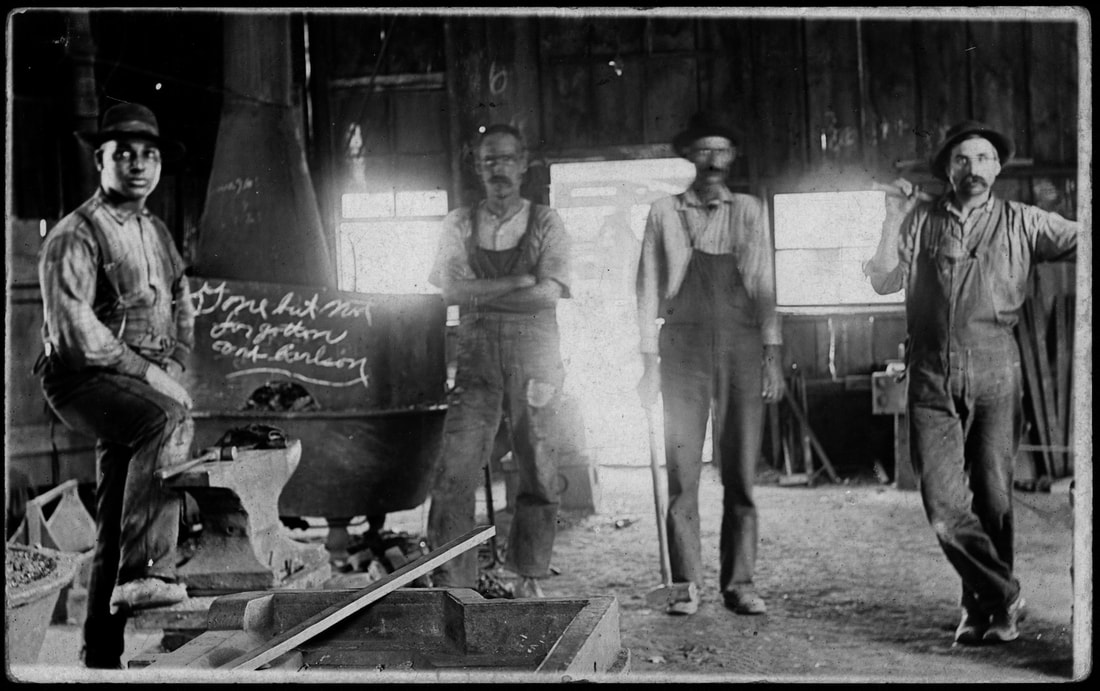

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! This week’s post marks the third and final post in our 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa (you can find the other posts here and here). This week’s post is by author Rachelle Chase. Even before moving to Iowa, the history of Buxton, Iowa, and its former residents fascinated Rachelle, and now that she has become an Iowa resident, she is determined to help share their story. Rachelle is the author of multiple fiction books and the non-fiction book, Lost Buxton. In 1900, Consolidation Coal Company established one of the most unique towns in Iowa: Buxton. Spanning 8,600 acres in Monroe County and 1,600 acres in Mahaska County, along with a population that grew to 5,000, Buxton became the largest unincorporated town in Iowa. Though the town itself was different from most other coal mining towns, Buxton is renowned for its large African American population. For the first 10 years, African Americans made up 55% of the population and remained the largest ethnic group until 1914. A Planned Town The typical mining town featured hastily constructed houses, a company store, a small school, a tavern, a union hall, and a church. Buxton was not “typical.” Buxton residents enjoyed 1-1/2 story houses which were maintained by the company, a company store that rivaled department stores, three two-story schoolhouses, a two-story high school, a three-story YMCA, and more than 10 churches. According the September 18, 1903 edition of the Iowa State Bystander, Superintendent Ben C. Buxton “designed and superintended the laying out of the town, the plans and construction of the buildings, the location and equipment of the mines, the water supply, the drainage and all the many interesting details ...” Buxton, Iowa, looking north. “Boy’s Y” (rectangular white building, left), YMCA (far left), W.H. Wells Company Store (center). The company store burned down in 1911 and was replaced with a brick building and renamed Monroe Mercantile Company Store. Courtesy: Michael W. Lemberger. A Prosperous Town As mentioned in previous posts, mining was often seasonal, which resulted in a reduced demand for coal in the warmer months. This was not the case in Buxton. Since Consolidation Coal Company was owned by the Chicago & North Western Railroad and trains required a constant supply of coal, men in Buxton worked year-round, earning $40-$100 every two weeks. “The miners received excellent pay according to the economy at that time,” said Reuben Gaines Jr., a successful African American businessman in Buxton, in an undated memoir. “In any event or manner the money flowed freely.” There was no shortage of ways residents in Buxton could spend money. They could shop at more than 40 independent businesses, plus the company store. “You could buy anything in that company store, from a diaper pin to a coffin,” said Kietzman. “The company had its own morticians and own mortuary. They had a shoe department, shoe repair department, furniture, hardware, groceries, cooking ware, clothing, and yard goods. The company store had a bank in it, the company office, a soda fountain where they served lunches.” A Racially Integrated Town Former residents—both black and white—agreed that Buxton was integrated and that any segregation that did exist, such as separate churches, was by choice. The company awarded housing on a first-come, first-served basis; 16 of the 85 company store clerks were black; black men and white men worked in the mines in neighboring “rooms”; black children and white children were taught by black and white teachers; and residents attended public events—baseball games, movies, parades, and picnics—sitting or standing wherever they desired. Believed to be blacksmith’s shop in Buxton, Iowa. Courtesy: State Historical Society of Iowa Residents also remembered interracial marriages. “There were a lot of interracial marriages down there...” said Oliver Burkett, an African American resident. “There was Charlie King, he was a black man, he married a white woman. Hobe Armstrong, he was a black man and he married a white woman. George Morrison, he was married to a white woman.” Carl Kietzman, previously quoted, was married to an African American woman. African Americans Thrived In addition to miners, there were many African American professionals and business owners in Buxton. African American professionals included doctors, lawyers, a dentist, pharmacists, constables, teachers, commercial and rental property owners, an insurance agent, company store clerks and at least one manager, a bank manager, a cigar maker, a postmaster, a mine engineer, two justices of the peace, barbers, a tailor, and many entrepreneurs. Black-owned businesses included hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, confectionaries, a bakery, drug stores, pool halls, dance halls, a music store, a photography and printing business, a meat market or two, millinery shops, and at least four newspapers. The End of Buxton By 1918, the mines near Buxton were almost completely played out and the company had moved operations to Consol, located 18 miles southwest of Buxton, and Bucknell/Haydock. By 1922, Buxton was a ghost town. Miners and their families had moved to other cities in Iowa and beyond in search of work or had moved to the company’s new towns. But by 1927, the continuing decline in coal demand and the negative perception of Iowa coal, plus labor problems, resulted in the shutdown of remaining mines. Consol and Bucknell/Haydock, like Buxton, were gone. The company store’s stone warehouse, the largest remaining structure in Buxton, Iowa in 2016. Source: Rachelle Chase For many African American residents, leaving Buxton was like stepping back in time. Jim Crow laws, segregation, extreme racism, and menial jobs awaited them, leaving many feeling like Susie Robinson. “There’s no place that’s ever going to be like Buxton,” said Robinson. “That’s the best place that I’ve ever been, Buxton.” If you would like to learn more about Buxton, Rachelle’s book, which uses rare photographs and quotes from former residents to tell its unique history, can be found on Amazon. You can also learn more about Rachelle and her books on her webpage.

I hope you’ve enjoyed our mining series as much as I have, and many thanks to our guest authors Darcy and Rachelle!

2 Comments

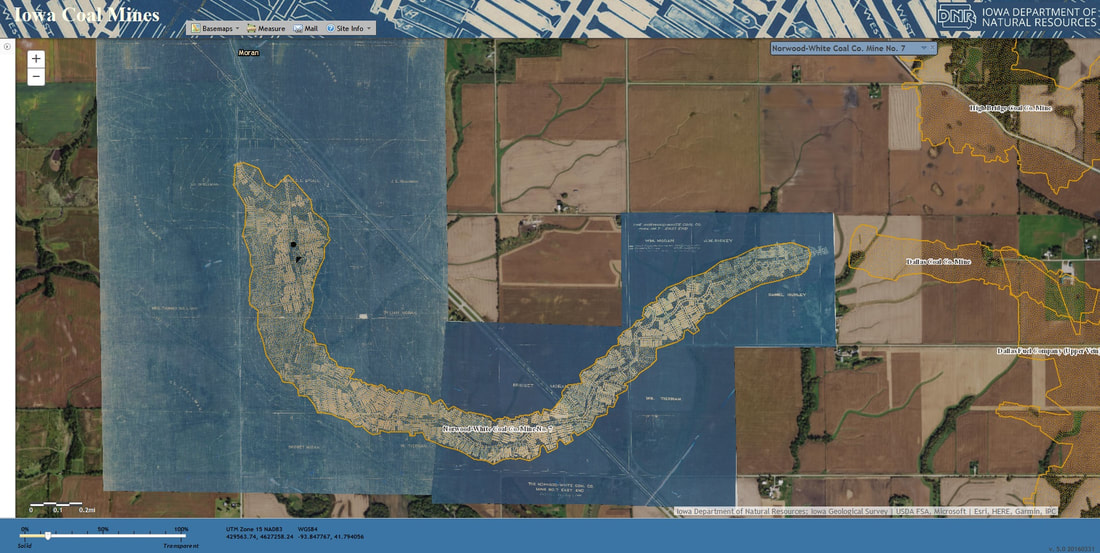

Welcome back to the Hometown Heritage blog! I am particularly excited for this week’s post, as it marks the first in a 3-part series on the abandoned towns and the history of coal mining in Iowa. I hope you enjoy! Norwood-White #7 Coal Mine and employees on October 4, 1939, near Moran, IA. This photo was taken about a year before the mine closed. If you recognize a miner, please comment below or send the name to [email protected]. As with many other small towns in Iowa, Perry owes part of its origins to coal mining. By 1895, Iowa had 342 coal mines that employed over 6000 miners. Thirty years later, at the height of coal mining, twice as many people were employed as miners, with coal production steadily declining in the years after. The coal industry attracted many immigrants to Iowa. One of the interviews in Hometown Heritage’s collection is with a former miner who worked near Moran, which is a largely abandoned mining community south of Woodward that today consists of only a few remaining houses. He describes a culturally and ethnically diverse group of miners at Moran – roughly 25% Northern European (Irish, English, Welsh), 25% Eastern European (Yugoslavian and Czech), 25% Italian, and 25% African American. The multicultural nature of the workforce was acknowledged by the unions, who published the United Mine Workers Journal in English, Italian, and Slovakian in 1917. This publication was important for miners, as it included information on where work could be found and places to avoid due to strikes or overcrowding, as well as obituaries, cartoons, and even poetry. Life in the mines was hard work. Dangerous gases were a problem, as well as collapses and accidents. Physical injuries, such as hernias, were also common. Former miners recall workers, especially immigrants, being cheated by mining companies. In spite of these dangers, Dorothy Schwieder, who interviewed former Italian-American miners for her 1982 paper in The Annals of Iowa, suggested that some immigrants preferred working in the mines over factories. Down in the mines, they could work more independently and with less supervision, rather than working in a factory with a supervisor standing right over their shoulder. Many miners started working when they were teenagers and some as young as 9 years old. Older miners were often assisted by younger brothers or sons, which allowed the younger boys and men to learn the trade. The extra hands also benefited the older miners, who were able to produce more coal and increase their paychecks, since miners were often paid by the cart-load of coal. Miners generally made between $5.50 – 7.50 per day, but as with most people, they saw these wages fall during the Depression years. While miners often worked 8 hours a day – eating their lunches far below ground – their days were considerably longer. One former miner remembers leaving his house at 6 am, changing clothes at the camp wash house, waiting and riding into the mines together with other miners, working 8 hours, waiting and riding back out, returning to the wash house for a bath and change of clothes, and getting home around 9 pm. Iowa coal wasn’t well known for its favorable properties. B.P. Fleming, a professor who taught at the University of Iowa, wrote a paper in 1927 which listed its negative attributes. Iowa coal has high ash and iron content, which makes it less efficient to burn. Our coal also has a high moisture level, which made it difficult to sell. If the coal was dry, it crumbled easily, which led to the suggestion that coal be stored underwater. But if the coal was fresh out of the ground (or water), it weighed extra because of the absorbed water, resulting in unhappy buyers. Perhaps the biggest problem was that Iowa coal also had a high sulfur content, which made it smell when burnt and also introduced the possibility of spontaneous combustion. Fleming noted that “it is no uncommon thing to see a carload of Iowa coal come into the yards on fire.” But Iowa coal was not necessarily worse than the poorly graded coal from other states, so it was used locally in houses or industrial plants where people would put up with its poorer qualities in exchange for its lower price. As a result of this local use, however, mines often shut down in the summer – when Iowan’s needed less coal – so many miners found themselves unemployed and looking for temporary work. Location of the Norwood-White Coal Mine #7 near Moran, IA. The diagonal line going through the image is Highway 141, between Woodward and R22, and today, commuters drive over this abandoned mine on their way to Des Moines. Source: https://programs.iowadnr.gov/maps//coalmines/# The Norwood-White Mine #7, located near Moran, was in operation from 1919 – 1940 and employed around 250 miners. While not the largest mine in Iowa, it was 340 acres, consisted of two levels, and had a shaft depth of 205 ft. It was first opened in 1917, but production was halted when miners encountered an underground lake. One former miner remembers divers exploring the lake to see what was down there. Eventually, the Norwood-White company put a cement shaft through this underground body of water, allowing the miners to access the coal below. The Moran mine was closed in 1940 due to an underground fire. While valiant efforts were put forth to contain the blaze – one miner remembers a Woodward fire truck being driven into the mine to try to put it out – the fire was so hot that it burnt the slate on the mine roof. The mine, and some equipment (including tools that the miners paid for themselves), had to be abandoned. The Norwood-White Mine #7 had a fairly long life, since mines most were generally open for only 10 years. As a result, the camps and communities in which miners lived – places which contained housing, schools, taverns, restaurants, and stores – could also be short lived, as the miners moved on if other work was not close by. These ghost towns were often quickly dismantled and reclaimed by nature, with little trace of the bustling community that once was. Former site of Norwood-White Mine #3, Moran, IA, now farm ground. Next week, tune in for a guest post written by author and Dallas County historian Darcy Maulsby, who will discuss coal mining in Dallas County, including mines located in Waukee, Van Meter, and Woodward/Granger! In the meantime, below are just a few of the local Iowa museums that have great displays on coal mines:

|

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

All Rights Reserved, Fullhart Carnegie Charitable Trust, 2014-2023

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

This website is possible with the support of the

Dallas County Foundation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed