Hosting Strangers

JOHN KUO WEI TCHEN, CLEMENT A. PRICE CHAIR OF PUBLIC HISTORY AND HUMANITIES, RUTGERS UNIVERSITY – NEWARK

JOHN KUO WEI TCHEN, CLEMENT A. PRICE CHAIR OF PUBLIC HISTORY AND HUMANITIES, RUTGERS UNIVERSITY – NEWARK

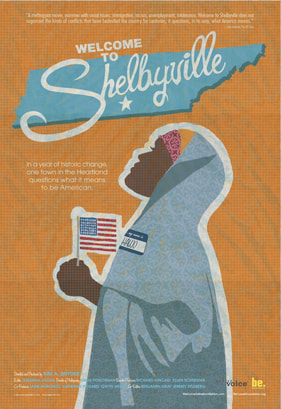

Courtesy of Active Voice and Because Foundation

Courtesy of Active Voice and Because Foundation

Kim A. Snyder’s Welcome to Shelbyville explores the story of a small town in Tennessee during the opening years of the 21st century. Located just sixty miles from Nashville, Shelbyville is a “buckle of the bible belt” town where Christian religious influence is particularly noticeable. When the local Tyson’s corporation brings in hundreds of Somali refugees of Muslim faith to work in its chicken processing plant, Shelbyville’s longtime residents struggle with how best to integrate them.

The film opens to Miss Luci’s ESL (English as a Second Language) class of Somali refugees. That ESL class rivets me. I see myself in Miss Luci and I see myself in these Somalis. You too may identify with them – or perhaps with one or more of the other residents of the community we meet in the film: the white reporter whose article in the town newspaper ignites debate and controversy; the town’s white mayor who says, “We don’t know them and it scares me”; an African American resident who says, “They like things the way it is”; a man with a Hispanic accent who says, “I tell them it’s a matter of time”; the pastor of a white congregation who asks his parishioners, “How do I deal with something deeply ingrained in me?”; and a Somali woman who wonders aloud, “I don’t know what’s wrong.”

Welcome to Shelbyville exemplifies the process of reflecting back and forth across divides in social and cultural backgrounds, and also demonstrates a consistent theme in the history of the United States. Each era in U.S. history has seen new immigrant groups enter a country already diverse through regional differences, previous voluntary and involuntary migrations, and indigenous populations.

With each new arrival to Shelbyville in recent years, of first Latino and then the more recent Somalian immigrants settling there, a claim of greater belonging and prior rights are made. We gain hints of previous conflicts and histories that point to how Shelbyville’s demographics have evolved. There is the story of Native Americans dispossessed by thirteen British colonies and those settlers’ ongoing expansion westward. This is, after all, the home of Andrew Jackson and his exile of the Cherokee on the “Trail of Tears.” We know African Americans were both enslaved and some free here. And we know the whites in town are not especially wealthy. All have a history of hard-earned gains. Unease across social, ethnic, racial and religious divides is prevalent.

The historical background that underlies the experiences of Shelbyville’s residents over generations is key to understanding the different points of view that each of its residents expresses. Who considered these lands and waters home, and at what time? Who was welcomed on arrival, and who was not? And how over time, with each new group of arrivals, did the dynamics shift? As we begin to understand Shelbyville, we also get to reflect on where we each live in the United States, and how similar conflicts are played out in myriad ways throughout the country. Residents in communities, towns and cities from coast to coast understand their own time and place as having underlying, often unstated, beliefs about power, belonging and connection.

The film opens to Miss Luci’s ESL (English as a Second Language) class of Somali refugees. That ESL class rivets me. I see myself in Miss Luci and I see myself in these Somalis. You too may identify with them – or perhaps with one or more of the other residents of the community we meet in the film: the white reporter whose article in the town newspaper ignites debate and controversy; the town’s white mayor who says, “We don’t know them and it scares me”; an African American resident who says, “They like things the way it is”; a man with a Hispanic accent who says, “I tell them it’s a matter of time”; the pastor of a white congregation who asks his parishioners, “How do I deal with something deeply ingrained in me?”; and a Somali woman who wonders aloud, “I don’t know what’s wrong.”

Welcome to Shelbyville exemplifies the process of reflecting back and forth across divides in social and cultural backgrounds, and also demonstrates a consistent theme in the history of the United States. Each era in U.S. history has seen new immigrant groups enter a country already diverse through regional differences, previous voluntary and involuntary migrations, and indigenous populations.

With each new arrival to Shelbyville in recent years, of first Latino and then the more recent Somalian immigrants settling there, a claim of greater belonging and prior rights are made. We gain hints of previous conflicts and histories that point to how Shelbyville’s demographics have evolved. There is the story of Native Americans dispossessed by thirteen British colonies and those settlers’ ongoing expansion westward. This is, after all, the home of Andrew Jackson and his exile of the Cherokee on the “Trail of Tears.” We know African Americans were both enslaved and some free here. And we know the whites in town are not especially wealthy. All have a history of hard-earned gains. Unease across social, ethnic, racial and religious divides is prevalent.

The historical background that underlies the experiences of Shelbyville’s residents over generations is key to understanding the different points of view that each of its residents expresses. Who considered these lands and waters home, and at what time? Who was welcomed on arrival, and who was not? And how over time, with each new group of arrivals, did the dynamics shift? As we begin to understand Shelbyville, we also get to reflect on where we each live in the United States, and how similar conflicts are played out in myriad ways throughout the country. Residents in communities, towns and cities from coast to coast understand their own time and place as having underlying, often unstated, beliefs about power, belonging and connection.

Shelbyville ESL and US Civics Class. Photo credit: Greg Poschman

Shelbyville ESL and US Civics Class. Photo credit: Greg Poschman

On top of questions of dispossession and enslavement, two conflicting strains have historically run through America’s relationship with its new migrants. Our national ideal of open borders and our professed desire to share our freedoms with others (as inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, beckoning the world’s ‘huddled masses yearning to breathe free’) has alternated with periods of backlash and animosity toward newcomers, often from already assimilated communities. Despite our common thread – that the vast majority of Americans can trace their roots to foreign lands – the United States has periodically treated its newest residents with strong anti-“outsider” prejudice that has resulted at times in restrictive quotas, attempts at forced assimilation, outright hostility and violence, and forced deportations or internment.

Throughout American history, the record of America’s immigration policy has been a swinging door that often opens during periods of prosperity and trade expansion, but slams shut during times of economic uncertainty or war. The flow of European immigrants from Germany and Ireland in the first half of the 19th century was essentially unrestricted and fueled by the need for cheap labor during rapid industrialization. Between 1860 and 1915, another wave of European immigrants entered the United States from Russia, Austria, Eastern Europe, Italy and the Mediterranean. Although labor continued to be needed, there also were strong anti-immigrant feelings toward this new population – in large part because the new immigrants did not conform to the Nordic, mostly Protestant norm that had arrived earlier. And this, despite the fact that when the earlier migrants arrived, they were denigrated as well.

Examples of the door shutting in American history can be traced from the beginning of the nation, including the Naturalization Act of 1790, the rise of the anti-Irish Catholic Know Nothing Party in the mid-1800s, the Chinese Exclusion Acts first enacted in 1882, Congress’ passage of a literacy requirement for immigrants following WWI, the deportation of thousands of Mexican workers, many of them U.S. citizens, in 1921-30, and the forced internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during WWII.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, United States immigration policy was greatly influenced by the American eugenics movement. This movement took the racial theories developed by Linnaeus and others, and applied them to the development of a nation and its people. Eugenicist proponents in the United States and Europe believed that the human species should direct its evolution through selective breeding and the institutionalization and sterilization of those deemed “unfit.” They tended to believe in the superiority of the Protestant Nordic Germanic and Anglo-Saxon peoples. The eugenics-defined National Origins Quota of 1924-1965 was one of the lowest periods of immigration in U.S. history. Europeans became racialized and ranked: “Nordics” were prized, central Europeans were classified as lesser “Alpines,” and lowest were the “Mediterraneans.” It is not coincidence that the Quota was enforced after decades of massive immigration into America by people from Italy, Greece, Hungary, and all the eastern European countries. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act (known as the Hart-Cellar Act), however, repealed the closed-door policy that had been in place since the 1920s and opened up a new era of immigration and civil rights. The 1965 act established a preference system focusing on immigrants’ skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens or residents. These provisions helped create a new peak period of immigration that continues today, with 80% of current immigrants coming from Latin America and Asia.

Large-scale immigration since the 1970s has been made up of both legal, formerly excluded, and illegal flows. Today, the U.S is engaged in a public dialogue and debate on how to address the complexity of current immigration issues. The current period coincides with vast migrations globally, the United States’ transformation from a manufacturing to a 21st century knowledge-based economy, and the increasing reliance of many multi-national companies on manufacturing and assembly in other countries.

When immigration history is taught in schools and public forums, the story often depicts “waves” of new immigrants coming during different eras where they face both welcome and prejudice. Yet, this framing of the story of how the United States came to be often leaves out two critical aspects of our history. First, the reality of first peoples living and cultivating these continental lands and waters and being colonized often gets glossed over, while the story of how the United States began is shrouded in the mythos of Anglo-American “founding” fathers. The other aspect that is often marginalized when speaking of immigration is that of forced migrants, such as the indentured servants of the colonial era and the enslaved of the pre-Civil War period, neither of whom were “immigrants.” Our understanding of the past is more complete when we also recognize that the feeding and building of the U.S. nation was supported by the labor of both immigrants and the forced migrants who were enslaved. The American story of who is welcomed and who is not as we recount the history of immigration truly begins with the early “encounters” between Native peoples and Western traders, missionaries, and colonists from Europe. Native peoples share the experience of being the first “settlers” dealing with “newcomers.”

Throughout American history, the record of America’s immigration policy has been a swinging door that often opens during periods of prosperity and trade expansion, but slams shut during times of economic uncertainty or war. The flow of European immigrants from Germany and Ireland in the first half of the 19th century was essentially unrestricted and fueled by the need for cheap labor during rapid industrialization. Between 1860 and 1915, another wave of European immigrants entered the United States from Russia, Austria, Eastern Europe, Italy and the Mediterranean. Although labor continued to be needed, there also were strong anti-immigrant feelings toward this new population – in large part because the new immigrants did not conform to the Nordic, mostly Protestant norm that had arrived earlier. And this, despite the fact that when the earlier migrants arrived, they were denigrated as well.

Examples of the door shutting in American history can be traced from the beginning of the nation, including the Naturalization Act of 1790, the rise of the anti-Irish Catholic Know Nothing Party in the mid-1800s, the Chinese Exclusion Acts first enacted in 1882, Congress’ passage of a literacy requirement for immigrants following WWI, the deportation of thousands of Mexican workers, many of them U.S. citizens, in 1921-30, and the forced internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during WWII.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, United States immigration policy was greatly influenced by the American eugenics movement. This movement took the racial theories developed by Linnaeus and others, and applied them to the development of a nation and its people. Eugenicist proponents in the United States and Europe believed that the human species should direct its evolution through selective breeding and the institutionalization and sterilization of those deemed “unfit.” They tended to believe in the superiority of the Protestant Nordic Germanic and Anglo-Saxon peoples. The eugenics-defined National Origins Quota of 1924-1965 was one of the lowest periods of immigration in U.S. history. Europeans became racialized and ranked: “Nordics” were prized, central Europeans were classified as lesser “Alpines,” and lowest were the “Mediterraneans.” It is not coincidence that the Quota was enforced after decades of massive immigration into America by people from Italy, Greece, Hungary, and all the eastern European countries. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act (known as the Hart-Cellar Act), however, repealed the closed-door policy that had been in place since the 1920s and opened up a new era of immigration and civil rights. The 1965 act established a preference system focusing on immigrants’ skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens or residents. These provisions helped create a new peak period of immigration that continues today, with 80% of current immigrants coming from Latin America and Asia.

Large-scale immigration since the 1970s has been made up of both legal, formerly excluded, and illegal flows. Today, the U.S is engaged in a public dialogue and debate on how to address the complexity of current immigration issues. The current period coincides with vast migrations globally, the United States’ transformation from a manufacturing to a 21st century knowledge-based economy, and the increasing reliance of many multi-national companies on manufacturing and assembly in other countries.

When immigration history is taught in schools and public forums, the story often depicts “waves” of new immigrants coming during different eras where they face both welcome and prejudice. Yet, this framing of the story of how the United States came to be often leaves out two critical aspects of our history. First, the reality of first peoples living and cultivating these continental lands and waters and being colonized often gets glossed over, while the story of how the United States began is shrouded in the mythos of Anglo-American “founding” fathers. The other aspect that is often marginalized when speaking of immigration is that of forced migrants, such as the indentured servants of the colonial era and the enslaved of the pre-Civil War period, neither of whom were “immigrants.” Our understanding of the past is more complete when we also recognize that the feeding and building of the U.S. nation was supported by the labor of both immigrants and the forced migrants who were enslaved. The American story of who is welcomed and who is not as we recount the history of immigration truly begins with the early “encounters” between Native peoples and Western traders, missionaries, and colonists from Europe. Native peoples share the experience of being the first “settlers” dealing with “newcomers.”

Minister Stephen Caine and Imam Mohammed Ali. Photo Credit: Gary Poschman

Minister Stephen Caine and Imam Mohammed Ali. Photo Credit: Gary Poschman

Learning about the history of immigration in the United States and discussing the role migration plays today in shaping our society, it might be time to reframe how we tell our immigration stories. Rather than framing the discussion as one about borders and walls, emigration, refugees, and immigration, foreigners and citizens or “us” versus “them,” we could dig deeper to discuss the shared dynamic of migration, unsettling and resettling that we have all experienced. At the core is the question of kindness and of hospitality. How do we host the stranger? How do we behave as guests?

Boston College philosopher and storyteller Richard Kearney wants us each to explore the basic human, cross-cultural, and inter-personal challenge of “hosting the stranger.” He poses this foundational humanities question: “There are always more guests to be hosted, strangers to be welcomed as they arrive at the door bearing gifts or bringing challenges, asking for bread or refuge, questioning, calling, demanding, thanking.” Of course, each one of us is always shifting positions; at different times we are either strangers or hosts. This question of how to behave as host and guest has been a theme in the story of America since the Pilgrims. In Ric Burns and Li Shinyu’s The Pilgrims (2015) (PBS, American Experience) the Puritan-Patuxet Thanksgiving story is told from a new perspective, based on actual historical documents and current scholarship. New evidence suggests the first winter for the Puritans in what would eventually be New England was a tragic failure, stemming from uninformed decisions made by the group’s leaders. Most of the settlers starved, and many died. At the same time, the local Native American population was decimated by disease brought by the Europeans. In their telling, both Governor William Bradford and Increase Mather decided to obscure the truth. “What really happened gets completely dropped out of the history…. They had to make some kind of meaning out of that. It couldn’t just be a waste yard of bones for everyone,” says historian Kathleen Donegan.

As we keep in mind the ever-shifting dynamics of who is part of the host society and who can be considered a newcomer, Shelbyville becomes a more complex human story that unfolds as the film unfolds. By the end of the film, we witness the healing dynamic of welcoming and sharing stories when a Somali family invites longtime Shelbyville residents to their home for dinner. The newcomer initiates the hosting and welcomes the native as the guest. In this interchange of migrant and host, we, the viewers, also gain a feeling of renewal and rediscovery.

In the act of welcoming and extending hospitality to others, a deeper connection to the nourishing wells of being a human being can emerge. In Ric Burns’ Pilgrims, Historian Donegan describes this in the Pilgrims’ story: “They [both Pilgrims and Native Americans] had been in such misery and they had lost so many people. That day of Thanksgiving is also coming out of mourning. It’s also coming out of grief, and this abundance that is a relief from that loss.” At a moment of massive loss on both sides, the pilgrims grounded their faith with the profound Native American tradition of giving thanks.

Welcome to Shelbyville ends also with people sharing good food and drink. Conversations across shared bowls, platters, and desserts allow all of us to gain a deeper understanding of our own experiences as well as those of others. Honest interactions prepare us to deal with a faceted reality of multiple meanings and values. Are we prepared to deal with the complexities of a history of migration with multiple meanings, and also deal with being good guests and gracious hosts in this land where all of us have been, at some time, strangers?

Boston College philosopher and storyteller Richard Kearney wants us each to explore the basic human, cross-cultural, and inter-personal challenge of “hosting the stranger.” He poses this foundational humanities question: “There are always more guests to be hosted, strangers to be welcomed as they arrive at the door bearing gifts or bringing challenges, asking for bread or refuge, questioning, calling, demanding, thanking.” Of course, each one of us is always shifting positions; at different times we are either strangers or hosts. This question of how to behave as host and guest has been a theme in the story of America since the Pilgrims. In Ric Burns and Li Shinyu’s The Pilgrims (2015) (PBS, American Experience) the Puritan-Patuxet Thanksgiving story is told from a new perspective, based on actual historical documents and current scholarship. New evidence suggests the first winter for the Puritans in what would eventually be New England was a tragic failure, stemming from uninformed decisions made by the group’s leaders. Most of the settlers starved, and many died. At the same time, the local Native American population was decimated by disease brought by the Europeans. In their telling, both Governor William Bradford and Increase Mather decided to obscure the truth. “What really happened gets completely dropped out of the history…. They had to make some kind of meaning out of that. It couldn’t just be a waste yard of bones for everyone,” says historian Kathleen Donegan.

As we keep in mind the ever-shifting dynamics of who is part of the host society and who can be considered a newcomer, Shelbyville becomes a more complex human story that unfolds as the film unfolds. By the end of the film, we witness the healing dynamic of welcoming and sharing stories when a Somali family invites longtime Shelbyville residents to their home for dinner. The newcomer initiates the hosting and welcomes the native as the guest. In this interchange of migrant and host, we, the viewers, also gain a feeling of renewal and rediscovery.

In the act of welcoming and extending hospitality to others, a deeper connection to the nourishing wells of being a human being can emerge. In Ric Burns’ Pilgrims, Historian Donegan describes this in the Pilgrims’ story: “They [both Pilgrims and Native Americans] had been in such misery and they had lost so many people. That day of Thanksgiving is also coming out of mourning. It’s also coming out of grief, and this abundance that is a relief from that loss.” At a moment of massive loss on both sides, the pilgrims grounded their faith with the profound Native American tradition of giving thanks.

Welcome to Shelbyville ends also with people sharing good food and drink. Conversations across shared bowls, platters, and desserts allow all of us to gain a deeper understanding of our own experiences as well as those of others. Honest interactions prepare us to deal with a faceted reality of multiple meanings and values. Are we prepared to deal with the complexities of a history of migration with multiple meanings, and also deal with being good guests and gracious hosts in this land where all of us have been, at some time, strangers?