Immigration & Popular Culture

RACHEL LEE RUBIN, PROFESSOR OF AMERICAN STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY MASSACHUSETTS, BOSTON

RACHEL LEE RUBIN, PROFESSOR OF AMERICAN STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY MASSACHUSETTS, BOSTON

Courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films

Courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films

Popular culture has long helped create and define key moments in immigration history (see Charlie Chaplin’s 1917 silent comedy, The Immigrant, in which the Tramp plays an immigrant fresh off the boat who must learn to survive in the foreign culture of New York City). It has provided, for better or worse, guidelines of behavior and manners for new settlers looking for clues on how to be American; and it has shaped how native-born Americans understand immigrants and immigration.

“Popular culture” (commonly written as “pop culture”) refers to the attitudes, ideas, images, perspectives and other phenomena within mainstream culture that have been manufactured by diverse mass media outlets, including entertainment (film, theater, television, radio), music, fashion, food and more. For more than a century, immigrants have been at the heart of the production and consumption of popular culture in the United States. For example, the early history of American films and the myths they enthroned were directly influenced by the experiences of the immigrants who created and ran Hollywood. In the early 20th century, immigrants and the sons of immigrants from Europe – including George and Ira Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and Harold Arlen – made up a large percentage of the word- and music-smiths writing songs for Tin Pan Alley and Broadway’s musical revues. Musical forms carried to America by immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean in the second half of the twentieth century influenced American jazz, rock, rhythm and blues, and country music. Hip Hop, the most significant American musical form of the past forty years was shaped, to a large degree, by the contributions of migrants from Jamaica, other islands in the Caribbean, and various parts of Latin America.

A multidirectional national conversation about immigration and Americanness has long played out on the popular culture landscape, centering on three major questions. What does the world of popular culture tell immigrants about what it means to be “American”? How have immigrants shaped the production of popular culture, and what industries, art forms and technological advances have been particularly congenial or hostile to them? How has popular culture, at different times, depicted immigrants and the immigrant experience? A study of these questions offers a road map of what we might call the “cultural imaginary” of immigrant life in America: where the real and the representational make and remake each other, where individual lives and creations come into productive conflict with institutional requirements and prescriptions.

A striking example of how popular culture has been a site for understanding the issues of immigration can been found in movies. In the relatively short time since their invention at the end of the nineteenth century, movies have rapidly evolved from a temporary novelty to one of the most dominant visual forms of modern popular culture worldwide. Beginning a few years after a draconian immigration law was enacted in 1924, the film industry embarked on a decades-long process of figuring out what the earlier waves of migration meant for American culture. One key element in this cultural reckoning was the gangster film, packed with immigrant characters.

Such films as Scarface (1932), The Public Enemy (1931), and Little Caesar (1931) represent (or offer thinly-veiled versions of) Italian, Irish and Jewish gangsters who struggle to achieve class mobility through crime and violence. The films pay lip service to film codes of the time – usually by having the key gangster characters die – but they also became the first major film genre to enshrine ethnic heroes. Movie reviewers were startled to find audiences cheering the gangster protagonists openly in theaters.

In American cinema and television, science fiction as a genre became an especially important site for exploring issues of “otherness” in American society. Within this genre, “aliens” populate science fiction plot lines, with the threat of alien invasion a popular theme. Filmmakers have dramatically expressed American fears of outsiders with “aliens” acting as proxy for immigrant newcomers. The popular movie Men in Black II (2002), for instance, features Agent J and Agent K who work for a secret government agency that both regulates and hides the presence on earth of “aliens.” In short, they work for an intergalactic immigration bureau.

In the movie, transport to the United States has evolved from a trans-Atlantic ship to Ellis Island, to intergalactic spacecraft touching down at a hidden government site somewhere in Manhattan. The climactic fight scene that ends the film takes place around the Statue of Liberty – a reference to and revision of the statue’s significance in earlier immigration narratives. In this crucial scene the special agents bounce rays of a special gun – a “neuralyzer” – against the statue, so that the torch sends out beams that wipe clean the memory of all in the area. In Men in Black II concerns about dangerous outsiders are neutralized through a process which ensures they will leave elements of their home culture behind.

American popular culture’s engagement with immigration was not limited to the explicit narratives of movies. Popular culture has continuously confronted and explored the question of immigration in every form, from comic books to professional sports, from children’s toys to advertising. Popular culture operates as what can be called a collective processing site where both producers and consumers use these cultural expressions to understand what is happening and to respond to it.

Popular culture’s processing of immigration is a common task of music, for instance. Popular music is full of lessons about immigration, ranging from the Eastern European immigrants who dominated Tin Pan Alley to rapper M.I.A.’s sly 2007 song (and accompanying video) “Paper Planes,” to the extremely popular Broadway musical Hamilton. A particularly rich example is country singer Merle Haggard’s 1978 song “The Immigrant.” On the level of lyrics, the song sympathetically confronts the exploitation of undocumented farm workers, noting wryly that after they are sent back to Mexico they’ll be brought back when the mansion-dwelling landowners need them. Haggard also invokes Mexican immigration sonically through the song’s instrumentation, which includes Mexican-style guitar and rhythms. And another layer of meaning was added when Chicano singer Johnny Rodriguez covered the song.

Popular culture’s processing of immigration includes the first comic strip, Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow Kid, which made its appearance in 1895. Yellow Kid featured a child protagonist who dwelled in the dirty and chaotic “Hogan’s Alley”; through the misadventures of a range of street urchins, this new, peculiarly American form explored the pressing issues of ethnicity, urbanity and global migration that continue to shape comics. For instance, Los Bros Hernandez’s graphic novel series Love and Rockets, first published in 1981, takes up issues of migration, identity, and power in a compelling way, deftly folding elements of superhero comics into a historically detailed presentation.

Processing immigration takes the form of young adult literature, such as Aliya Husain’s book about being a Muslim teenager in the United States, Neither This Nor That. And it takes the form of sports fandom, when immigrant communities feel represented by players from their birthplace and cheer them on – or when professional athletes immigrate to the United States in order to play organized sports. It takes the form of fashion – sometimes controversially, when questions of cultural appropriation are raised by, for instance, white Americans wearing dreadlocks.

“Popular culture” (commonly written as “pop culture”) refers to the attitudes, ideas, images, perspectives and other phenomena within mainstream culture that have been manufactured by diverse mass media outlets, including entertainment (film, theater, television, radio), music, fashion, food and more. For more than a century, immigrants have been at the heart of the production and consumption of popular culture in the United States. For example, the early history of American films and the myths they enthroned were directly influenced by the experiences of the immigrants who created and ran Hollywood. In the early 20th century, immigrants and the sons of immigrants from Europe – including George and Ira Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and Harold Arlen – made up a large percentage of the word- and music-smiths writing songs for Tin Pan Alley and Broadway’s musical revues. Musical forms carried to America by immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean in the second half of the twentieth century influenced American jazz, rock, rhythm and blues, and country music. Hip Hop, the most significant American musical form of the past forty years was shaped, to a large degree, by the contributions of migrants from Jamaica, other islands in the Caribbean, and various parts of Latin America.

A multidirectional national conversation about immigration and Americanness has long played out on the popular culture landscape, centering on three major questions. What does the world of popular culture tell immigrants about what it means to be “American”? How have immigrants shaped the production of popular culture, and what industries, art forms and technological advances have been particularly congenial or hostile to them? How has popular culture, at different times, depicted immigrants and the immigrant experience? A study of these questions offers a road map of what we might call the “cultural imaginary” of immigrant life in America: where the real and the representational make and remake each other, where individual lives and creations come into productive conflict with institutional requirements and prescriptions.

A striking example of how popular culture has been a site for understanding the issues of immigration can been found in movies. In the relatively short time since their invention at the end of the nineteenth century, movies have rapidly evolved from a temporary novelty to one of the most dominant visual forms of modern popular culture worldwide. Beginning a few years after a draconian immigration law was enacted in 1924, the film industry embarked on a decades-long process of figuring out what the earlier waves of migration meant for American culture. One key element in this cultural reckoning was the gangster film, packed with immigrant characters.

Such films as Scarface (1932), The Public Enemy (1931), and Little Caesar (1931) represent (or offer thinly-veiled versions of) Italian, Irish and Jewish gangsters who struggle to achieve class mobility through crime and violence. The films pay lip service to film codes of the time – usually by having the key gangster characters die – but they also became the first major film genre to enshrine ethnic heroes. Movie reviewers were startled to find audiences cheering the gangster protagonists openly in theaters.

In American cinema and television, science fiction as a genre became an especially important site for exploring issues of “otherness” in American society. Within this genre, “aliens” populate science fiction plot lines, with the threat of alien invasion a popular theme. Filmmakers have dramatically expressed American fears of outsiders with “aliens” acting as proxy for immigrant newcomers. The popular movie Men in Black II (2002), for instance, features Agent J and Agent K who work for a secret government agency that both regulates and hides the presence on earth of “aliens.” In short, they work for an intergalactic immigration bureau.

In the movie, transport to the United States has evolved from a trans-Atlantic ship to Ellis Island, to intergalactic spacecraft touching down at a hidden government site somewhere in Manhattan. The climactic fight scene that ends the film takes place around the Statue of Liberty – a reference to and revision of the statue’s significance in earlier immigration narratives. In this crucial scene the special agents bounce rays of a special gun – a “neuralyzer” – against the statue, so that the torch sends out beams that wipe clean the memory of all in the area. In Men in Black II concerns about dangerous outsiders are neutralized through a process which ensures they will leave elements of their home culture behind.

American popular culture’s engagement with immigration was not limited to the explicit narratives of movies. Popular culture has continuously confronted and explored the question of immigration in every form, from comic books to professional sports, from children’s toys to advertising. Popular culture operates as what can be called a collective processing site where both producers and consumers use these cultural expressions to understand what is happening and to respond to it.

Popular culture’s processing of immigration is a common task of music, for instance. Popular music is full of lessons about immigration, ranging from the Eastern European immigrants who dominated Tin Pan Alley to rapper M.I.A.’s sly 2007 song (and accompanying video) “Paper Planes,” to the extremely popular Broadway musical Hamilton. A particularly rich example is country singer Merle Haggard’s 1978 song “The Immigrant.” On the level of lyrics, the song sympathetically confronts the exploitation of undocumented farm workers, noting wryly that after they are sent back to Mexico they’ll be brought back when the mansion-dwelling landowners need them. Haggard also invokes Mexican immigration sonically through the song’s instrumentation, which includes Mexican-style guitar and rhythms. And another layer of meaning was added when Chicano singer Johnny Rodriguez covered the song.

Popular culture’s processing of immigration includes the first comic strip, Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow Kid, which made its appearance in 1895. Yellow Kid featured a child protagonist who dwelled in the dirty and chaotic “Hogan’s Alley”; through the misadventures of a range of street urchins, this new, peculiarly American form explored the pressing issues of ethnicity, urbanity and global migration that continue to shape comics. For instance, Los Bros Hernandez’s graphic novel series Love and Rockets, first published in 1981, takes up issues of migration, identity, and power in a compelling way, deftly folding elements of superhero comics into a historically detailed presentation.

Processing immigration takes the form of young adult literature, such as Aliya Husain’s book about being a Muslim teenager in the United States, Neither This Nor That. And it takes the form of sports fandom, when immigrant communities feel represented by players from their birthplace and cheer them on – or when professional athletes immigrate to the United States in order to play organized sports. It takes the form of fashion – sometimes controversially, when questions of cultural appropriation are raised by, for instance, white Americans wearing dreadlocks.

Courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films

Courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films

And perhaps at the very heart of the give-and-take between new immigrant cultures and mainstream American popular culture is the story of food. Throughout United States history, as new immigrants settled in diverse cities, towns and regions, new foods and recipes were introduced to American cuisine. The integration of various styles of ethnic cooking into American eating habits expanded tremendously in the 19th and 20th centuries, proportional to the influx of immigrants from many different nations. The growing numbers of immigrants from Asia, the Middle East and Latin America to the United States in the wake of changes to immigration law in 1965 has led to an increased incorporation of those ethnic cuisines into the Anglo-American diet. One interesting signpost: by the early 1990s salsa had overtaken ketchup in retail sales.

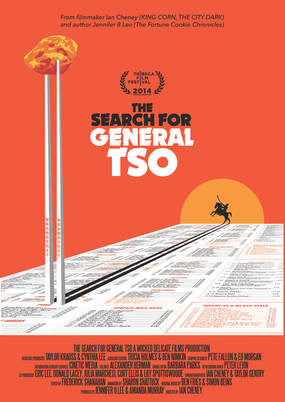

Popular culture’s processing of immigration especially takes the form of ethnic restaurants; for instance, a significant story is told by the fact that a neighborhood that once had multiple Italian restaurants might now have multiple Vietnamese restaurants, as new generations of immigrants establish themselves. The documentary The Search for General Tso focuses on the story of one type of ethnic restaurant in the United States that has perhaps been the most successful in gaining mainstream popularity. The documentary uses the ubiquitous Americanized dish, General Tso’s chicken, as a lens onto a larger story of immigration, adaptation and innovation to American popular culture. Early on, the film poses the question, “If Chinese Americans comprise only 1% of the U.S. population, why are there Chinese restaurants in almost every city across America?”

Popular culture’s processing of immigration especially takes the form of ethnic restaurants; for instance, a significant story is told by the fact that a neighborhood that once had multiple Italian restaurants might now have multiple Vietnamese restaurants, as new generations of immigrants establish themselves. The documentary The Search for General Tso focuses on the story of one type of ethnic restaurant in the United States that has perhaps been the most successful in gaining mainstream popularity. The documentary uses the ubiquitous Americanized dish, General Tso’s chicken, as a lens onto a larger story of immigration, adaptation and innovation to American popular culture. Early on, the film poses the question, “If Chinese Americans comprise only 1% of the U.S. population, why are there Chinese restaurants in almost every city across America?”

Courtesy of Bullfrog Films

Courtesy of Bullfrog Films

The Search for General Tso tells the story of the origins and rise of Chinese restaurants in America – but it can’t help being also an immigration story. The discriminatory legislation of the 1880s that forced Chinese migrants out of the labor market also specified what businesses they could and could not own. Restaurants and laundries being among the few allowed, the recipe for success began in San Francisco, with Chinese settlers eventually dispatched around the country in order to avoid growing competition at home. By the film’s end, we come to understand how food created a bridge that eventually surpassed many immigrants’ fondest dreams of success and assimilation, and changed Americans’ eating habits forever.

The work of popular culture often is about the day to day processing of the role of immigration in defining American society. A striking example of the work done by popular culture in processing immigration appeared in the Washington Post in 2017. Acknowledging a cultural conversation that began with the Trump administration’s attempts to establish new immigration policies, the Post declared in a headline: TV Dramas and Sitcoms are Suddenly All About Immigration. The cultural conversation, then, usefully and urgently continues.

The work of popular culture often is about the day to day processing of the role of immigration in defining American society. A striking example of the work done by popular culture in processing immigration appeared in the Washington Post in 2017. Acknowledging a cultural conversation that began with the Trump administration’s attempts to establish new immigration policies, the Post declared in a headline: TV Dramas and Sitcoms are Suddenly All About Immigration. The cultural conversation, then, usefully and urgently continues.