Help Wanted? Immigration & Work

VINCENT J. CANNATO, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON

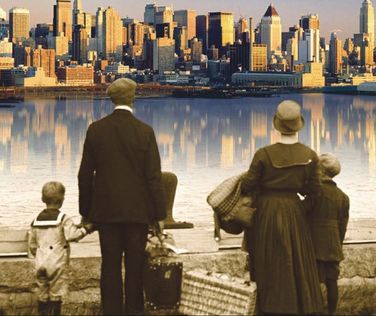

America’s contemporary conception of immigration is expressed in the words of Emma Lazarus’s poem, inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty in 1903: “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free / The wretched refuse of your teeming shore / Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.” The Lazarus poem posits immigrants as refugees fleeing oppressive homelands in search of freedom on American shores. Immigration, therefore, becomes primarily a political movement. This story links immigrants with earlier European settlers, such as the Pilgrims and Puritans, who sought to escape religious persecution in Europe for the chance to practice religious freedom in America.

There is an element of truth to the tale. America has received and integrated many waves of refugees since the time of the Pilgrims: Germans who left their homeland after the failed revolution of 1848; Russian Jews escaping the pogroms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Hungarians fleeing after the failed 1956 uprising against Communism; Vietnamese boat people in the late 1970s crossing the Pacific in the aftermath of the war; and more recently, Somali immigrants fleeing a civil war. The idea and reality of political refugees remains an important rationale for immigration to the United States.

There is an element of truth to the tale. America has received and integrated many waves of refugees since the time of the Pilgrims: Germans who left their homeland after the failed revolution of 1848; Russian Jews escaping the pogroms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Hungarians fleeing after the failed 1956 uprising against Communism; Vietnamese boat people in the late 1970s crossing the Pacific in the aftermath of the war; and more recently, Somali immigrants fleeing a civil war. The idea and reality of political refugees remains an important rationale for immigration to the United States.

Despite these examples, however, since the early 19th century the pattern of immigration to the United States has been driven more by economic motivations than political ones. Most immigrants to the United States come with the desire to economically better their lives and the lives of their families. On the flip side, native-born Americans have long depended on new immigrants to help build the nation by farming open land, working in factories, and performing other low-skilled work that more affluent and established native-born Americans shy away from.

An amusing story from the early 1900s tells of the immigrant who had been told that American streets were paved with gold, a well-known tale exaggerating the wealth and opportunities to be found in America. The story goes that when the immigrant arrived in America, he found not only that the streets were not paved with gold, but that many of them were not paved at all and that he was expected to pave them.

The story reflects a basic truth about the relationship between immigration and the American economy. Many immigrants saw America as a land of riches that would improve their own economic situations, a view that often hit hard against the realities of life in industrial America. Native-born Americans, on the other hand, saw the newcomers as a necessary labor force for the heavy work of building the railroads, bridges, tunnels, subways, and roads that made America into an industrial powerhouse, as well as working in the mines, sweatshops, and slaughterhouses that supplied America’s consumers and businesses.

An amusing story from the early 1900s tells of the immigrant who had been told that American streets were paved with gold, a well-known tale exaggerating the wealth and opportunities to be found in America. The story goes that when the immigrant arrived in America, he found not only that the streets were not paved with gold, but that many of them were not paved at all and that he was expected to pave them.

The story reflects a basic truth about the relationship between immigration and the American economy. Many immigrants saw America as a land of riches that would improve their own economic situations, a view that often hit hard against the realities of life in industrial America. Native-born Americans, on the other hand, saw the newcomers as a necessary labor force for the heavy work of building the railroads, bridges, tunnels, subways, and roads that made America into an industrial powerhouse, as well as working in the mines, sweatshops, and slaughterhouses that supplied America’s consumers and businesses.

Immigrant women working as seamstresses. Photo credit, Culver Pictures

Immigrant women working as seamstresses. Photo credit, Culver Pictures

And work they did. Historian Tyler Andbinder has shown in his study of New York’s Emigrant Savings Bank in the mid-19th century that Irish immigrants who had fled the potato famine for America worked hard: the men primarily as laborers and clerks; the women as domestic servants and seamstresses. Their bank savings were testament to their hard work. The median initial deposit of these working-class immigrants was $70, or about $1,900 in today’s dollars. The median high balance for each account was $203 or about $5,600 in today’s dollars. Immigrants were not only earning money and making the slow climb up the socioeconomic ladder, they were also contributing their labor to their adoptive land and helping to grow the American economy.

The “Second Industrial Revolution” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought the largest wave of immigrants to America, reaching a high of 1.2 million new settlers in 1907 alone. Immigrants were attracted to the many jobs available in American factories and mines, low-wage jobs that still provided more money and opportunity than could be found at home. Upton Sinclair’s classic 1906 novel The Jungle highlights the importance of immigrant labor in industrial America, as it tells the tragic story of Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant working under terrible conditions in a Chicago slaughterhouse.

Italian immigrants often relied on “padrones,” many of whom were immigrants themselves, to find work. Such “padrones” served as middle-men between immigrants looking for jobs and American employers who needed a source of low-wage labor. While most came to America to stay, marry or bring their families over and establish new roots, other immigrants were known as “birds of passage.” They came to America for a few years to work and save enough to return to their homelands with an improved standard of living. Close to half of immigrants from Greece and Italy were classified as “birds of passage.” Even immigrants who were not birds of passage often sent money back to relatives in their home countries through remittances. These patterns can be seen not only among earlier immigrant groups, but also among contemporary ones today.

Immigrant women were an important part of the immigrant labor experience as well as men. Not only did they take care of their families, but they worked as seamstresses and domestic servants. Often all the women in a family would do ‘piecework’ in their tenement apartment – sewing individual garments and getting paid by the “piece.” The most famous – and most tragic – story of immigrant working women is New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. There, some 146 people, mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women who toiled in the sweatshop making women’s blouses, lost their lives. The tragedy helped spur the growth of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, to protect the right of sweatshop workers and improve their working conditions.

The “Second Industrial Revolution” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought the largest wave of immigrants to America, reaching a high of 1.2 million new settlers in 1907 alone. Immigrants were attracted to the many jobs available in American factories and mines, low-wage jobs that still provided more money and opportunity than could be found at home. Upton Sinclair’s classic 1906 novel The Jungle highlights the importance of immigrant labor in industrial America, as it tells the tragic story of Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant working under terrible conditions in a Chicago slaughterhouse.

Italian immigrants often relied on “padrones,” many of whom were immigrants themselves, to find work. Such “padrones” served as middle-men between immigrants looking for jobs and American employers who needed a source of low-wage labor. While most came to America to stay, marry or bring their families over and establish new roots, other immigrants were known as “birds of passage.” They came to America for a few years to work and save enough to return to their homelands with an improved standard of living. Close to half of immigrants from Greece and Italy were classified as “birds of passage.” Even immigrants who were not birds of passage often sent money back to relatives in their home countries through remittances. These patterns can be seen not only among earlier immigrant groups, but also among contemporary ones today.

Immigrant women were an important part of the immigrant labor experience as well as men. Not only did they take care of their families, but they worked as seamstresses and domestic servants. Often all the women in a family would do ‘piecework’ in their tenement apartment – sewing individual garments and getting paid by the “piece.” The most famous – and most tragic – story of immigrant working women is New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. There, some 146 people, mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women who toiled in the sweatshop making women’s blouses, lost their lives. The tragedy helped spur the growth of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, to protect the right of sweatshop workers and improve their working conditions.

Photo credit: NPS/Statue of Liberty NM

Photo credit: NPS/Statue of Liberty NM

Immigration to the U.S. increased dramatically beginning in the late 1800s. This new wave of newcomers included rising numbers of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, whose cultures and religious backgrounds (Catholic, Jewish, Greek Orthodox), were very different from the Anglo-Saxon Protestant American mainstream. This stirred the fears of native-born Americans and led to the rise of nativist sentiments.

Concerns about the perceived impact of immigrant labor on the economy led to a series of federal laws restricting immigration that began in the 1880s. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned the immigration of all Chinese laborers. Around 250,000 Chinese were living in the U.S. at this time, mostly concentrated on the West Coast. Many had come to help build the transcontinental railroad. Others worked as miners or operated laundries. That the law targeted only the Chinese betrays the racial biases of the law and its supporters, even though labor concerns played an important role in its passage. One of the law’s staunchest supporters was California labor leader (and Irish immigrant) Dennis Kearney, who railed against the migration of the Chinese “coolie,” whom he argued was nothing more than a “cheap working slave” whose presence in America widened “the breach between the rich and the poor, still further to degrade white Labor.”

Well into the 20th century, American labor unions often supported restricting immigration. A few years after the Chinese Exclusion Act, Congress passed the Alien Contract Labor Law, which barred American entry to immigrants who had already secured work under contract before their arrival. The bill was strongly supported by the nascent labor movement. American business, on the other hand, has generally looked favorably upon immigration as a source of low-wage labor, advertising overseas and using arrangements like the “padrone” system to encourage the immigration of laborers.

The quota laws of the 1920s, which would severely limit immigration for the next four decades, were largely based on racialist distinctions, privileging Northern European immigrants above those from southern and eastern Europe. The quota laws also completely shut the door to Asian immigration. However, demand for labor continued, and the quota limits did not apply to immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. Between 1910 and 1930, immigration from Mexico tripled. At the beginning of, and during World War Two, when much of the American labor force entered the military, the U.S. government negotiated with Mexico for the importation of temporary workers under the “Bracero” program. Some two million Mexican workers arrived between 1942 and 1964 to provide much needed agricultural labor in California and the Southwest. The program continued after the war ended as the labor needs continued, even with returning soldiers.

One can see the economic basis of American immigration by looking at the correlation between immigration rates and economic booms and busts. After every major economic downturn, immigration declined significantly, as potential immigrants saw fewer economic opportunities in the U.S. during lean years. From the Panic of 1837 to the Depression of 1893 to the Panic of 1907, each economic crisis saw declines in immigration rates of over forty percent. The Great Depression of the 1930s was even more dramatic. In 1933, only 23,000 immigrants arrived – down more than ninety percent from a decade earlier – and more people left the country than arrived.

This trend changed in the years after the 1965 Immigration Act. A look at the recessions of the 1970s or the Great Recession of 2008-9 shows no significant impact on legal immigration. (The number of undocumented immigrants did decline after 2008, however.) The major reason for this is that immigration visas since 1965 skew in favor of admitting relatives of those already in the country. Such family-sponsored visas made up almost two-thirds of all immigrants in 2015. Less than fifteen percent of those arriving that year received an employment-based visa. That is not to say that those arriving on family preference visas don’t work, but rather that their arrival to the U.S. is less dependent on the booms and busts of the U.S. economy and more reliant on family reunification.

Recent immigrants have played an important part in the nation’s economy. Unlike the immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries, today’s immigrants can be found at both ends of the wage spectrum. Many immigrants today are recruited by American high tech, health care, and financial companies to work in high-skilled jobs in technology, engineering, and medicine. At the other end, immigrants, both legal and illegal ones, also perform many low-skill, low-wage jobs, such as agricultural work and service jobs in hotels, hospitals, nursing homes and restaurants. Immigrants also create and run small businesses, from Indian-owned motels to Korean grocery stores and Vietnamese nail salons, to Cambodian donut shops and ethnic restaurants of all stripes across the nation.

Today, the debate over immigration is fueled by cultural and racial concerns, but also by economic ones. The tension between the need for inexpensive labor and the challenges of absorbing newcomers into American society continues to be a central issue in American policy. Are immigrants taking jobs from American workers? Do immigrants lower the wages of native-born workers? What is the impact of immigration on schools, hospitals and social welfare programs? What will be the impact on American agriculture and the health and service fields if large numbers of immigrants are no longer allowed into the country? Social scientists debate these economic impacts, but the work that immigrants do and their impact on the economy has been a central reality in the United States for two centuries and will continue to be a factor for the foreseeable future.

Concerns about the perceived impact of immigrant labor on the economy led to a series of federal laws restricting immigration that began in the 1880s. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned the immigration of all Chinese laborers. Around 250,000 Chinese were living in the U.S. at this time, mostly concentrated on the West Coast. Many had come to help build the transcontinental railroad. Others worked as miners or operated laundries. That the law targeted only the Chinese betrays the racial biases of the law and its supporters, even though labor concerns played an important role in its passage. One of the law’s staunchest supporters was California labor leader (and Irish immigrant) Dennis Kearney, who railed against the migration of the Chinese “coolie,” whom he argued was nothing more than a “cheap working slave” whose presence in America widened “the breach between the rich and the poor, still further to degrade white Labor.”

Well into the 20th century, American labor unions often supported restricting immigration. A few years after the Chinese Exclusion Act, Congress passed the Alien Contract Labor Law, which barred American entry to immigrants who had already secured work under contract before their arrival. The bill was strongly supported by the nascent labor movement. American business, on the other hand, has generally looked favorably upon immigration as a source of low-wage labor, advertising overseas and using arrangements like the “padrone” system to encourage the immigration of laborers.

The quota laws of the 1920s, which would severely limit immigration for the next four decades, were largely based on racialist distinctions, privileging Northern European immigrants above those from southern and eastern Europe. The quota laws also completely shut the door to Asian immigration. However, demand for labor continued, and the quota limits did not apply to immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. Between 1910 and 1930, immigration from Mexico tripled. At the beginning of, and during World War Two, when much of the American labor force entered the military, the U.S. government negotiated with Mexico for the importation of temporary workers under the “Bracero” program. Some two million Mexican workers arrived between 1942 and 1964 to provide much needed agricultural labor in California and the Southwest. The program continued after the war ended as the labor needs continued, even with returning soldiers.

One can see the economic basis of American immigration by looking at the correlation between immigration rates and economic booms and busts. After every major economic downturn, immigration declined significantly, as potential immigrants saw fewer economic opportunities in the U.S. during lean years. From the Panic of 1837 to the Depression of 1893 to the Panic of 1907, each economic crisis saw declines in immigration rates of over forty percent. The Great Depression of the 1930s was even more dramatic. In 1933, only 23,000 immigrants arrived – down more than ninety percent from a decade earlier – and more people left the country than arrived.

This trend changed in the years after the 1965 Immigration Act. A look at the recessions of the 1970s or the Great Recession of 2008-9 shows no significant impact on legal immigration. (The number of undocumented immigrants did decline after 2008, however.) The major reason for this is that immigration visas since 1965 skew in favor of admitting relatives of those already in the country. Such family-sponsored visas made up almost two-thirds of all immigrants in 2015. Less than fifteen percent of those arriving that year received an employment-based visa. That is not to say that those arriving on family preference visas don’t work, but rather that their arrival to the U.S. is less dependent on the booms and busts of the U.S. economy and more reliant on family reunification.

Recent immigrants have played an important part in the nation’s economy. Unlike the immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries, today’s immigrants can be found at both ends of the wage spectrum. Many immigrants today are recruited by American high tech, health care, and financial companies to work in high-skilled jobs in technology, engineering, and medicine. At the other end, immigrants, both legal and illegal ones, also perform many low-skill, low-wage jobs, such as agricultural work and service jobs in hotels, hospitals, nursing homes and restaurants. Immigrants also create and run small businesses, from Indian-owned motels to Korean grocery stores and Vietnamese nail salons, to Cambodian donut shops and ethnic restaurants of all stripes across the nation.

Today, the debate over immigration is fueled by cultural and racial concerns, but also by economic ones. The tension between the need for inexpensive labor and the challenges of absorbing newcomers into American society continues to be a central issue in American policy. Are immigrants taking jobs from American workers? Do immigrants lower the wages of native-born workers? What is the impact of immigration on schools, hospitals and social welfare programs? What will be the impact on American agriculture and the health and service fields if large numbers of immigrants are no longer allowed into the country? Social scientists debate these economic impacts, but the work that immigrants do and their impact on the economy has been a central reality in the United States for two centuries and will continue to be a factor for the foreseeable future.