Between Two Worlds

Lilia Fernandez, Associate Professor of History and Latino and Caribbean Studies, Rutgers University

Lilia Fernandez, Associate Professor of History and Latino and Caribbean Studies, Rutgers University

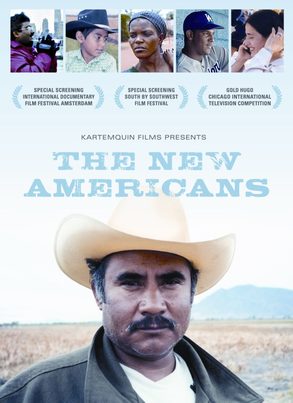

Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

The process of migration by definition involves encountering cultural change. When people leave their homelands and migrate to a new society they encounter new languages, foodways, customs, traditions, and social norms. For many, this presents a challenge: adapting to a foreign environment requires learning new social rules and practices and often new ways of behaving. For others, especially those who have some previous knowledge of their new adopted home, they may welcome such changes, especially if they offer new opportunities or freedoms that migrants did not enjoy in their home countries. Cultural adaptation and exchange, however, does not occur only in one direction. Immigrants contribute new ideas and practices to their adopted countries as well. They introduce new words into the dominant language, new foods, fashions, and forms of recreation. The process of migration produces complex dynamics with regard to one’s identity, sense of self, and sense of belonging.

Throughout the history of immigration to the United States, immigrants experienced varying degrees of adaption and assimilation to their new environment. The first Spanish, English, French, and Dutch settlers who came to the newly claimed European colonies arrived to a foreign setting where they had to learn how to adapt in order to survive. They depended primarily on the knowledge of native peoples, who taught them how to harvest native foods, raise new crops, and acclimate to the natural environment. While these original settler-colonists borrowed Native American words, practices, and ideas, however, they also intentionally tried to recreate their European societies in the colonies rather than fully assimilate into the existing Native world. The French, the Dutch, the Spanish, and the English brought their legal systems, religious beliefs, economic practices, and world views and imposed them (sometimes forcefully) on indigenous peoples. In this respect, the early colonists were distinct from later immigrants who have been expected to adapt their ways of life to American society much more fully.

By the first decades of the 1800s, a young American nation began to take shape and a distinctive “American” identity and culture emerged. Subsequent immigrants entered a society where they retained some aspects of their heritage and practices but also were expected to adopt “American” ways. The Irish and the Germans, for example, brought with them their own traditions and lifeways that influenced American culture, diets, and economic activity and were incorporated into the developing nation – our St. Patrick’s Day celebrations and taste for hamburgers and frankfurters are just a few examples. Many immigrants retained their Irish or German identity by building their own churches, publishing newspapers in their native languages, and maintaining strong bridges with family and friends back home. By the second and third generation, however, the children of these immigrants no longer considered themselves “Irish” or “German”; instead, they saw themselves as “Irish Americans” or “German Americans” or simply “Americans.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the source of migration to the United States shifted from Northern and Western Europe to Southern and Eastern Europe. The new populations – Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Italians, Slavs and Greeks, among others – similarly brought their traditions and ways of life. Many also tried to retain their connection to the heritage and culture of their original country by attending synagogues, churches, or social clubs where services were offered in their native languages. They produced a vibrant foreign language press and often lived among or socialized with fellow countrymen and women, allowing them to celebrate holidays or traditional festivals that they had observed back home. As the United States industrialized and technological advances increased communication and accessibility, Americans embraced a mass consumer culture. Across the country, in urban, rural and suburban areas, Americans began to participate in the same types of leisure and recreational activities – theatrical performances, motion pictures, dime store novels, and radio programs. They began shopping not only in local stores offering local products, but also through mail order catalogs or in department stores that offered a larger variety of merchandise. And they began buying national brand products and shopping at chain stores. As this mass culture proliferated, immigrants and their children faced increasing pressure to assimilate and acculturate to a new American society.

Throughout the history of immigration to the United States, immigrants experienced varying degrees of adaption and assimilation to their new environment. The first Spanish, English, French, and Dutch settlers who came to the newly claimed European colonies arrived to a foreign setting where they had to learn how to adapt in order to survive. They depended primarily on the knowledge of native peoples, who taught them how to harvest native foods, raise new crops, and acclimate to the natural environment. While these original settler-colonists borrowed Native American words, practices, and ideas, however, they also intentionally tried to recreate their European societies in the colonies rather than fully assimilate into the existing Native world. The French, the Dutch, the Spanish, and the English brought their legal systems, religious beliefs, economic practices, and world views and imposed them (sometimes forcefully) on indigenous peoples. In this respect, the early colonists were distinct from later immigrants who have been expected to adapt their ways of life to American society much more fully.

By the first decades of the 1800s, a young American nation began to take shape and a distinctive “American” identity and culture emerged. Subsequent immigrants entered a society where they retained some aspects of their heritage and practices but also were expected to adopt “American” ways. The Irish and the Germans, for example, brought with them their own traditions and lifeways that influenced American culture, diets, and economic activity and were incorporated into the developing nation – our St. Patrick’s Day celebrations and taste for hamburgers and frankfurters are just a few examples. Many immigrants retained their Irish or German identity by building their own churches, publishing newspapers in their native languages, and maintaining strong bridges with family and friends back home. By the second and third generation, however, the children of these immigrants no longer considered themselves “Irish” or “German”; instead, they saw themselves as “Irish Americans” or “German Americans” or simply “Americans.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the source of migration to the United States shifted from Northern and Western Europe to Southern and Eastern Europe. The new populations – Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Italians, Slavs and Greeks, among others – similarly brought their traditions and ways of life. Many also tried to retain their connection to the heritage and culture of their original country by attending synagogues, churches, or social clubs where services were offered in their native languages. They produced a vibrant foreign language press and often lived among or socialized with fellow countrymen and women, allowing them to celebrate holidays or traditional festivals that they had observed back home. As the United States industrialized and technological advances increased communication and accessibility, Americans embraced a mass consumer culture. Across the country, in urban, rural and suburban areas, Americans began to participate in the same types of leisure and recreational activities – theatrical performances, motion pictures, dime store novels, and radio programs. They began shopping not only in local stores offering local products, but also through mail order catalogs or in department stores that offered a larger variety of merchandise. And they began buying national brand products and shopping at chain stores. As this mass culture proliferated, immigrants and their children faced increasing pressure to assimilate and acculturate to a new American society.

Isreal and Ngozi Nwidor with their son Karm. Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

Isreal and Ngozi Nwidor with their son Karm. Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

To the children of immigrants, who saw their participation in consumer culture as a way to become “American,” the new mass culture was especially attractive. Young people clamored to see the latest movie shows, listen to popular music, and wear the latest fashions. This was particularly true during the 1920s, the “Flapper Age” or “Jazz Age.” The process of assimilating or acculturating into American society often produced generational tensions when immigrant parents, who often maintained more traditional and conservative views and ideas, hoped their children would retain their family’s original culture, religion, and heritage. Such conflicts between generations within immigrant families have persisted over the years and continue into the present.

While the children of immigrants have used mass culture as a way to assimilate more quickly into American society, immigrants have also influenced and changed what we define as “American culture.” Many musicians, writers, and theater performers at the turn of the century were recent immigrants who infused Yiddish, Italian, and Russian cultural elements into the art forms they produced. Immigrants also introduced new foods to the American diet – bagels, pierogis, spaghetti, egg rolls and latkes. Even as Americans gravitated to an emerging mainstream popular culture, immigrants continued to reshape what was seen as “American” in various ways.

While the children of immigrants have used mass culture as a way to assimilate more quickly into American society, immigrants have also influenced and changed what we define as “American culture.” Many musicians, writers, and theater performers at the turn of the century were recent immigrants who infused Yiddish, Italian, and Russian cultural elements into the art forms they produced. Immigrants also introduced new foods to the American diet – bagels, pierogis, spaghetti, egg rolls and latkes. Even as Americans gravitated to an emerging mainstream popular culture, immigrants continued to reshape what was seen as “American” in various ways.

Ngozi and fellow nurse at the hospital. Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

Ngozi and fellow nurse at the hospital. Courtesy of Kartemquin Films

In the second half of the twentieth century, growing numbers of people from Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East began migrating to the United States. They encountered many of the same dilemmas and dynamics that earlier immigrants did. Some have tried hard to preserve their religious traditions, or encouraged their children to marry within their ethnic, national, or religious group. Still others hope to instill a sense of their ethnic or national identity in their U.S.-born children. Many quickly discover, however, that their children are more fluent in English and serve essential roles as translators between their families and mainstream American society. Second and third-generation children of immigrants rapidly adopt American gender norms, notions of appropriate family relations, and dating practices. They also marry outside of their parents’ cultural group at higher rates.

The question of identity continues to be a complex one for immigrants and their children. Individuals’ perspectives on assimilation and acculturation can vary depending on how loyal one is to his/her maternal or paternal heritage, how much exposure one has had to various cultural influences, and one’s aspirations and expectations in the United States. Regardless, the experience of living between two worlds for immigrants and their children continues to create challenges for individuals as much as it enriches the greater American society.

The question of identity continues to be a complex one for immigrants and their children. Individuals’ perspectives on assimilation and acculturation can vary depending on how loyal one is to his/her maternal or paternal heritage, how much exposure one has had to various cultural influences, and one’s aspirations and expectations in the United States. Regardless, the experience of living between two worlds for immigrants and their children continues to create challenges for individuals as much as it enriches the greater American society.